Although the analysis and recommendations relating to cross-border surrogacy arrangements are contained in the last chapter of the Final Report, this does not mean that the issue is less important than the rest of the report. Far from it, international arrangements are increasingly common, and it is thought that almost half of surrogate-born children in the UK are born following an international arrangement. It may therefore be perceived that international arrangements need to fall within the scope of the general recommendations.

However, as acknowledged by the Law Commissions, there is limited scope to legislate or provide oversight for things that happen outside of the jurisdiction. It was stated that the jurisdictions intended parents engage with surrogacy in are almost invariably countries that permit surrogacy on a commercial basis, carrying with it risks associated with exploitation and trafficking. It is therefore important that domestic law strikes a balance between the policy issues involved where there is a risk of exploitation in the arrangement, whilst acknowledging that international surrogacy arrangements are a frequent occurrence, and that the legal framework needs to support the welfare of the child born of that arrangement.

Taking from the Final Report, it was stated:

One of the main aims of the law reforms we recommend in this Report is to encourage intended parents in the UK who wish to enter into surrogacy agreements to do so in the UK, rather than overseas. This aim to encourage domestic agreements is closely linked to our other primary aim, which is to ensure that surrogate-born children, surrogates and intended parents in the UK benefit from appropriate protection, through screening and safeguarding and support. In contrast, international surrogacy is beyond jurisdiction in the UK, and we cannot address the risks of exploitation in international surrogacy arrangements.

page 489 of the Final Report.

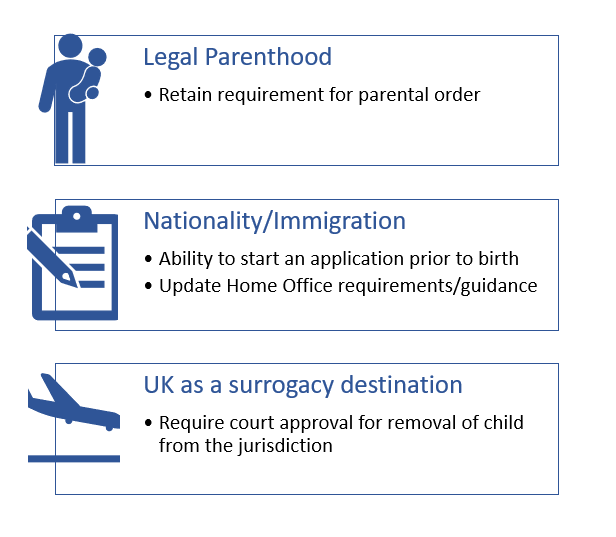

Notwithstanding these concerns, provisional proposals and final recommendations have been made to ease the process by which intended parents can bring the child into the UK after an international surrogacy arrangement has taken place. The operational recommendations relating to acquiring nationality, passports and visas, as well as regulating when intended parents travel into the UK to access surrogacy services, will be explored in subsequent posts.

Aside from the amendments to operational processes, in the 2019 Consultation Paper the Law Commissions also provisionally proposed changes as to how legal parenthood following an international surrogacy arrangement is recognised. Despite ultimately changing their view in the Final Report, the provisional proposals highlight the restrains of the current process – and the failure to ultimately recommend any changes to this area will create a two-tier system, depending upon where the child was born.

The current legal framework

At present, the same rules relating to parenthood apply irrespective of where the surrogacy arrangement took place. This means that the surrogate will be the legal mother, and her spouse/civil partner would be the second parent (if applicable). If the surrogate is not married, it is possible that the genetic intended parent would be the legal father. In order to remove the surrogate’s legal parenthood, a parental order needs to be obtained.

Details of the parental order process are detailed in a separate post, and the same general approach applies. However, in relation to international arrangements, there are certain requirements under s54 that often require closer attention or pose additional concerns:

- The surrogate must consent to the parental order being granted: given that the surrogate will not be within the UK, and may have limited English speaking/writing abilities, it may be the case that consent is harder to obtain. There have been reported cases where the intended parents have not been able to locate the surrogate, or where there have been concerns over the documentation providing consent. However, this concern is mitigated by the fact that s54(7) allows the court to dispense with the requirement for consent from the surrogate where she cannot be located.

- The intended parents must not have paid beyond reasonable expenses, unless the court authorises the payment: given that international arrangements are invariably commercial in nature, the courts regularly need to approve payments that have been made to the surrogate which exceed the concept of ‘reasonable expenses’. Consultee responses to the Consultation Paper reported costs ranging from £38,000 – £167,000 – far exceeding an interpretation of reasonable expenses.

Aside from the difficulties that international arrangements may pose in the s54 parental order process, the issue is also exacerbated by the differences in how jurisdictions allocate parenthood. Some jurisdictions recognise intended parents as the legal parents from birth (such as in the Ukraine and California). Despite this, that allocation of parenthood does not apply in the UK. This means that when the child returns to the UK, they could effectively become parentless: the surrogate is the legal parent in the eyes of domestic law, but in their jurisdiction, they are not, nor have they ever been, recognised as the legal parent of the child.

Recognising these challenges, the Law Commissions made provisional proposals in relation to the recognition of legal parenthood following international surrogacy arrangements.

The Provisional Proposals

In the 2019 Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions put forward a provisional proposal to provide the Secretary of State with the power to recognise intended parents as the legal parents of the child in the UK where that parenthood had been validly established in the country of birth. This would, in defined circumstances, have removed the necessity for the intended parents to apply for a parental order. The power to recognise such parenthood would have arisen where the Secretary of State is satisfied that the domestic law and practice in the country in question provides protection for the surrogate and child that is of a standard that is at least equivalent to protections in the UK.

The view held by the Law Commissions at the time of the Consultation Paper was that this would alleviate time, cost and pressures on intended parents who have already gone through the process of establishing parenthood in the child’s country of birth.

Most of the consultees who were not opposed to surrogacy in principle were in support of this provisional proposal. However, there were concerns around the risks of exploitation not being sufficiently combatted by this proposal, and there were also concerns around whether such a procedure would align with the human rights standard in this area: the UN Special Rapporteur has commented that legal parenthood following surrogacy should not be transferred without judicial oversight, and this process would act contrary to that approach. On a more practical level, some consultees commented that it would be difficult for the Secretary of State to assess what an ‘equivalent’ level of protection in the jurisdiction would look like.

The Final Report

Ultimately, the provisional proposal was not recommended in the Final Report. In addition to the consultation responses above, persuaded by the argument made by Dr Alan Brown, the Law Commissions stated that such a process would be ‘fundamentally at odds with one of the underlying policy objectives of our reforms’ which is to encourage domestic surrogacy in order to combat the risks of exploitation.

As such, the Final Report makes no recommendations as to changing how legal parenthood is allocated following international surrogacy arrangements. Such arrangements are not eligible on the new pathway, and intended parents will therefore need to continue in applying for a parental order to be recognised as the child’s legal parents.

In the context of the wider reforms proposed to the parental order process, there are a couple of recommendations that are worth restating in relation to international arrangements.

First, it is recommended that all international arrangements continue to be allocated to High Court judges: this ensures the judge will have the benefit of experience in such cases and will be able to make other orders as necessary.

Secondly, there are recommendations to amend the s54 requirements. These recommendations include the ability to dispense with the surrogate’s consent where the welfare of the child necessitates it, and the removal of the issue surrounding payments to the surrogate from the determination of parenthood. Whilst the case law demonstrates that the court can liberally interpret ‘reasonable expenses’, or retrospectively approve payments that have been made, removing the requirement in its entirety provides a clearer divide between the issues of parenthood and payments.

Commentary

The failure of the Law Commissions to recommend wholescale reform to allocation of legal parenthood following international surrogacy arrangements is not necessarily surprising. There are a myriad of issues, both legal and political, that need to be considered, and any reform that would make international surrogacy more accessible would run contrary to the aim of the project to encourage intended parents to remain within the UK to access surrogacy. However, expecting all intended parents to turn to domestic surrogacy is a highly optimistic (and ultimately unrealistic) goal – particularly whilst there is a perceived shortage of willing surrogates within the UK.

It is hoped that the recommendations made to ease the administrative process for the child to acquire nationality and documentation to enter into the UK after birth will help to minimise some of the current pressures faced by intended parents. These will be explored in a subsequent post, but fall far short of the more radical provisional proposal made in relation to legal parenthood.

Leave a comment