The new pathway, which would recognise the intended parents as the child’s legal parents from birth, would be hoped to capture most domestic surrogacy arrangements. The details of the recommendations for the new pathway have been covered by a previous post. However, the necessity for judicial oversight and determination of legal parenthood will remain in some cases. There are three particular circumstances where a parental order would still be required:

- International surrogacy arrangements, which would not be eligible for the pathway.

- When a surrogate exercises her right to withdraw consent on the pathway.

- Arrangements that operate without oversight of a Regulated Surrogacy Organisation and are therefore not approved for the pathway.

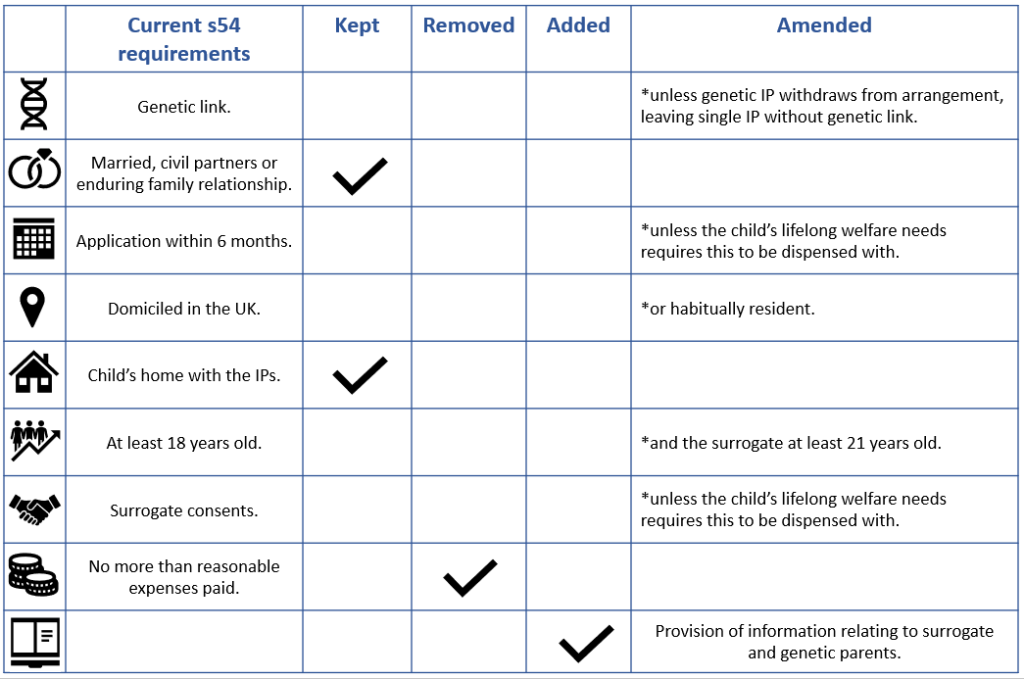

As such, the Final Report makes recommendations for reforming the parental order process. The recommendations cover changes to the existing statutory criteria contained within s54 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 and the court procedure.

The current operation of s54

Given that the surrogate and her spouse, if applicable, will be the legal parents of any child born as a result of a surrogacy arrangement, it is necessary for the intended parents to obtain a parental order after the child’s birth. The parental order extinguishes existing legal parenthood and recognises the intended parents as the legal parents of the child.

The prescriptive requirements contained within s54 for the granting of a parental order must be considered by the court, in conjunction with the obligation for the lifelong welfare of the child to be the paramount consideration. As explored in more detail in an another post, this has led to a situation where some of the statutory requirements have been liberally interpreted, or set aside, in order to satisfy the welfare of the child by recognising the intended parents as the legal parents.

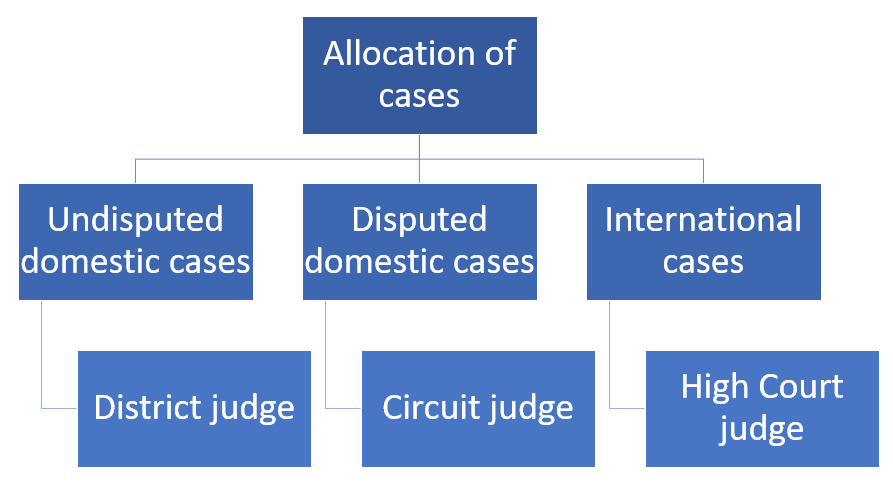

At present, the allocation of parental order cases depends upon the nature of the arrangement. Domestic surrogacy arrangements where there is no dispute are allocated to lay justices (magistrates) for determination. Other domestic arrangements, where there is a dispute as to the allocation of legal parenthood, are allocated to a circuit judge. All international surrogacy cases are allocated to a High Court judge in the Family Division, and following the case of Re Z (Foreign Surrogacy: Allocation of Work: Guidance on Parental Order Reports), it was recommended that such cases be allocated to a select group of High Court judges with experience of parental order applications.

Who can apply?

Under the existing legal framework, because the surrogate is the legal mother at birth, it is the intended parents who apply for the parental order. Since 2018 it is possible for a single intended parent to apply under s54A, and for both individual and two applicants, there must be a genetic link between an intended parent and the child. There would be various changes to eligible applicants within the recommendations:

First, despite consulting on the issue, the Final Report recommends that the requirement for a genetic link between an intended parent and the child is retained. However, there is one limited exception to this requirement: in cases where two intended parents began the journey, but the genetically related intended parent subsequently withdraws from the arrangement, the remaining intended parent without a genetic link would still be able to apply for a parental order to be recognised as the child’s legal parent. To do so, the Law Commissions argue, would be to ensure the child’s welfare is best served. However, where there is an absent intended parent, it is recommended that they be joined to the proceedings so that the court can then determine whether to grant a parental order to one or both of the individuals.

Secondly, for joint applicants, there is a recommendation to depart from the current judicial interpretation relating to the relationship between the applicants. S54(2) requires the applicants to be married, civil partners or in an enduring family relationship, and in both Re F & M (Children) (Thai Surrogacy) and Re DM v SJ, the court granted parental orders to the couples despite the fact that it was only one intended parent who began the surrogacy journey, with the partner becoming involved at a later stage. In moving away from this current approach, the recommendation is that if an individual was not a party to the original agreement, they should not be permitted to be an applicant for the parental order. This recommendation is proposed on the basis that the individual would have lacked intention to be a parent at the time of conception, which is the key basis upon which legal parenthood is recognised in such cases.

Thirdly, and arguably the biggest change, the Final Report recommends that a surrogate be able to apply for a parental order. This could arise in two situations:

- If after 6 months, the intended parents have not applied for a parental order, the surrogate would be able to apply for one on their behalf. It may be in the surrogate’s interests to do so, to remove her status as the child’s legal parent.

- If after the birth of the child, the surrogate exercises her right to withdraw consent, the intended parents would still be the child’s legal parents. By withdrawing her consent, which must be done within a 6-week time frame, she would then be able to apply for a parental order to be recognised as the child’s legal parent.

Reforming the s54 requirements

An overview of the changes that would be made to the requirements under s54 in light of the recommendations has already been provided. Nearly all of the current s54 requirements have been amended to some extent, and these are considered in more detail below.

Kept

- For intended parents applying for a parental order, the requirement for the child’s home to be with the applicants would be retained. In circumstances where the surrogate is applying for the parental order, this requirement would not apply.

- For joint applicants, they must still be married, in a civil partnership or in an enduring family relationship.

Kept but changed

- As discussed above, the requirement for a genetic link between an intended parent and child is to be retained under the recommendations. The only exception to this requirement would be where a non-genetic intended parent is pursuing a parental order alone after the genetic parent withdrew from the arrangement.

- The Law Commissions provisionally proposed removing the 6-month time limit, given the consistent approach of the court in granting parental orders out of time on the basis of the welfare of the child. Nonetheless, the Final Report recommends retaining the time limit, but with an explicit statutory provision allowing the court to dispense with the requirement where it is in accordance with the lifelong welfare of the child. This revision would therefore see the current judicial approach being reflected in the legislation, and was regarded as meeting the best interests of the child whilst still encouraging intended parents to apply for the parental order promptly.

- Similarly as with the time limit, it is proposed that the consent of the surrogate be retained as a requirement for a parental order, but with a statutory ability for the court to dispense with it where the child’s welfare necessitates it. This can be seen as an extension to the existing s54 wording, which permitted the surrogate’s consent be dispensed with where she cannot be found or lacks capacity, and aligns the provisions on consent with adoption proceedings.

- The existing statutory requirement for the applicant to be domiciled in the UK would be expanded so that the test of connection could also be met through habitual residence, aligning more closely with other family law provisions.

- The intended parents must still be at least 18 years old, but there is a recommended additional age imposition that the surrogate be at least 21 years old at the time of entering into the agreement.

Removed

- The current requirement that the surrogate has not been paid more than reasonable expenses, unless payment has been authorised by the court, would be removed under the recommendations. Instead, the issue of payments would be dealt with separately to the allocation of legal parenthood. More information about the recommendations relating to payments is covered in a separate post.

Added

- The Final Report does recommend one new requirement: that, at the time of making the application, the applicants provide information about the surrogate and genetic parents for inclusion on the Surrogacy Register (or HFEA Register for gamete donors). A separate post will explore this in more detail, but the recommendation is centred on ensuring the surrogate-born child has access to full information relating to their origins. If information about a gamete donor is not available (for example, because the surrogacy arrangement took place overseas where donation can happen on an anonymous basis), it would still be possible to grant a parental order provided that the Surrogacy Register records that anonymous donated gametes were used.

Reforming the procedure

In relation to the allocation of cases, it is recommended that cases no longer be allocated at magistrate level. Uncontentious cases would be likely to follow the new pathway, thus meaning arrangements left to be resolved via the parental order process are more likely to be complex or disputed. Therefore, domestic cases would be heard, by default, by district judges and referred to a circuit judge in the event of an opposition to the application.

It is recommended that international arrangements continue to be allocated to High Court judges. Various benefits for this approach were cited in the Full Report, including the benefit of experience, the ability for the judges to make other orders if necessary, and the fact that they create precedent and would be more likely to be reported.

One further recommendation relating to procedure is to reverse Rule 16.35(5) of the Family Procedure Rules. Under this Rule, the report made by the parental order reporter (responsible for acting on behalf of the child and safeguarding the child’s interests) remains confidential unless the court orders it to be released. In practice, it is often released, but not until the final hearing. Nearly all consultees agreed with the provisional proposal to change this Rule. Resultantly, it would be reversed so that the report is automatically released to all parties at the start of the proceedings.

Concluding Comments

Many of the recommended changes to the existing requirements appear to be an attempt to align the statutory wording with current judicial practice, particularly in allowing criteria to be set aside on the basis of the lifelong welfare of the child. There are some particularly notable changes, however. First is the ability to grant a parental order even without the consent of the surrogate: this is a change in the current judicial approach of the surrogate’s consent being considered as a bright line rule, and demonstrates a significant shift in how parenthood would be determined. Secondly, the removal of the issue of payments from the allocation of parenthood means that there is clearer separation of the policy concerns around payment and the welfare of the child. Whilst the recommended scheme relating to payments remains controversial, it is a positive step to see this removed as a criteria relating to the allocation of parenthood. Finally, the recommended new requirement for applicants to provide information for entry onto the Surrogacy Register recognises the significance of information relating to origins for surrogate-born children.

It can be hoped that flexibility within the requirements would operate in the same way as present, ultimately allowing a parental order to be granted in order to meet the lifelong welfare needs of the child.

Leave a reply to Case Update: Domicile Determination (X & another v Z & another) – reforming surrogacy law Cancel reply