Payments that can be made to surrogates is a controversial area within the context of surrogacy law reform. The current legislation arguably hinders the best interests of the child, and has received criticism for being unclear, lacking transparency, and creating a problematic link with the intended parents financial conduct and the obtainment of a parental order.

In response to these concerns, the Final Report recommended a regulated, documented, and enforceable approach to payments to surrogates. Proposed reforms include mandatory payments to the surrogates; enforcement of agreed payments; recovery of payments available to both parties; civil penalties for misconduct; and a financial annex (a document within the Regulated Surrogacy Statement regarding their financial agreement).

This post analyses the issues with payments under the current law, specifically by analysis of s54 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 (HFE Act). Following this, the 2019 Provisional Proposals will be laid-out, to then compare with the recommendations in the Final Report

The current law

Presently, payments made through surrogacy arrangements can be approved or authorised under to s54 HFE Act. s54(8) states that to grant a parental order:

The court must be satisfied that no money or other benefit (other than for expenses reasonably incurred) has been given or received by either of the applicants for or in consideration of—

(a) the making of the order,

(b) any agreement required by subsection (6),

(c) the handing over of the child to the applicants, or

(d) the making of arrangements with a view to the making of the order,

unless authorised by the court.

The court must be satisfied that the intended parents gave no monetary or non-monetary compensation to the surrogate other than “expenses reasonably incurred”. The same provision, however, also allows the court to authorise payments beyond reasonable expenses in order to grant a parental order. Notably, “expenses reasonably incurred” is undefined. Therefore, the contradictory and vague nature of the legislation has resulted in a lack of clarity concerning which payments are permitted within the current system.

Additionally, agreements relating to payments are often undocumented. Therefore, it is difficult for courts to assess whether payments made to surrogates are in-fact “expenses reasonably incurred”. Further, payment agreements under the current law are unenforceable resulting in a lack of security for the surrogate. This could result in a situation where they could be left financially worse-off for having acted as a surrogate.

s54(8) of the HFE Act can also present issues with international surrogacy agreements, where intended parents often make payments to surrogates that are outside of the UK’s legislative scope but permitted in other jurisdictions. It can be difficult to enforce the limitations intended under the legislation as a result of the fundamental role parental orders have on the child’s parenthood, and therefore best interests. This was recognised in the case of Re X and Y (2008), where Mr Justice Hedley stated –

The difficulty is that it is almost impossible to imagine a set of circumstances in which by the time the case comes to court, the welfare of any child (particularly a foreign child) would not be gravely compromised (at the very least) by a refusal to make an order.

Re X & Y, para 28.

Therefore, the courts has recognised that the current law, aiming to prohibit payment to surrogates, can conflict with the best interests of the child. Resultantly, the prohibition intended under s54(8) can be seen as ineffective. Significantly, the Law Commissions are unaware of any parental orders being refused on the basis of payments made to the surrogate.

The 2019 Consultation Paper

In the Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions did not put forward any provisional proposals relating to payments to surrogates, recognising the contentious nature and diverse views on the issue. Instead, they proposed several categories of payment and invited consultees to comment on whether such payments should be permitted, and whether the payment agreements should be regulated and enforceable.

The Final Report

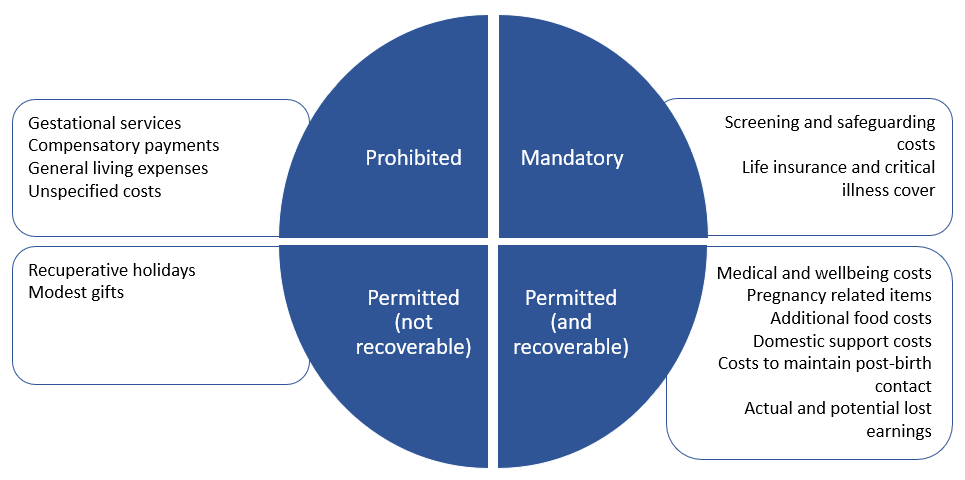

The Final Report includes twelve categories of permitted payments, including mandatory payments, which would be permitted and enforceable. The new scheme would also permit gifts and recuperative holidays which would be optional and unenforceable.

The specified permitted payment categories are listed below:

| Permitted Payments | Description |

| Costs related to the decision to enter the agreement | E.g., travel costs, and other expenses involved with the decision to enter into a surrogacy arrangement. |

| Domestic support costs | Expenses for domestic assistance for the surrogate during pregnancy and postpartum period. |

| Additional dietary requirements | The surrogate may require additional dietary requirements during the pregnancy. |

| Costs of maintaining contact between parties | Costs associated with maintaining contact between the surrogate, intended parents, and child after birth. |

| Loss of earning and lost employment potential | The surrogate may lose earnings due to missed work related to the surrogacy arrangement, and this expense is covered. |

| Medical and wellbeing costs | Medical expenses related to the pregnancy, including doctor’s visits, medications, and wellbeing expenses. |

| Modest gifts for the surrogate | Intended parents may choose to give the surrogate modest gifts. These would not be enforceable. |

| Pregnancy-related items | E.g., maternity clothing or prenatal vitamins. |

| Travel and occasional accommodation costs | Travel fees necessary to travel to medical appointments or to see the intended parents, or occasional accommodation costs if necessary. |

| Modest recuperative holiday for the surrogate | Intended parents may offer a modest recuperative holiday after the pregnancy. This would not be enforceable. |

| Safeguarding and screening costs of the pathway | Costs associated with the mandatory safeguarding and screening via the new pathway. This payment would be mandatory. |

| Insurance for the surrogate | Insurance coverage for the surrogate which could operate for potentially 2 years post-birth. This payment would be mandatory. |

Prohibited payments:

Any payments not within the above defined permitted categories of payments, would be a prohibited payment. There are four specified prohibited payments detailed in the Report:

- Gestational services payments (payments made to the surrogate for her role in acting as a surrogate and carrying the child)

- Compensatory payments for pain and inconvenience of pregnancy

- General living expenses such as mortgage/rent payments, or telephone bills

- Payments for unspecified costs (e.g., an allowance or lump sum to the surrogate)

The Law Commissions believe that to allow these payments would be to ‘enable commercial surrogacy and run the risk of exploitation’. Resultantly, they view that prohibiting these payments would ensure that arrangements remain altruistic in nature.

The logistics of the payments scheme

For surrogacy arrangements on the new pathway, the payments to be made would be agreed by all parties, and approved by the RSO (Regulated Surrogacy Organisation), for inclusion in the RSS (Regulated Surrogacy Statement) as a financial annex. Any subsequent change, or additional payment, would need to be notified and approved by the RSO. 6-12 weeks after the birth of the child, the intended parents would be required to make a statutory declaration that the payments made accord with the financial annex. In parental order cases, the intended parents would be required to report the payments made as part of the application, along with a statement of truth.

The Law Commissions recommended that payments can only be for re-imbursement of actual costs within the lawful payment categories, as opposed to an allowance which is a common practice currently. To avoid the surrogate being out of pocket, a ‘float’ would be permitted, in which the intended parents can provide an advance sum of money for costs expected to arise throughout the surrogacy agreement.

Notably, there is no statutory limitation placed on the amount of money that the intended parents are permitted to pay the surrogate, as long as the payments fall within the permitted categories. However, as the payments would be approved by the RSO and documented in the RSS, this would still promote clarity and transparency of payment agreements made between the parties.

Enforcement of the payment scheme

Ensuring compliance with the payment scheme would be essential, but there was a recurring theme throughout the Report that the Law Commissions wanted to separate the issue of payments from the allocation of parenthood, as is currently the case under s54(8). Subsequently, various enforcement mechanisms were recommended.

First, if the intended parents do not make the statutory declaration as explained above, or make a false declaration, they would commit a criminal offence that could result in a fine and a record on their criminal record. For intended parents following the parental order process, if their payment report is not accurate, they would be in contempt of court.

Secondly, the RSOs would play a fundamental role in the payment scheme and would face regulatory sanctions for not fulfilling their role. They would be expected to advise and guide parties through their financial agreement and authorise or reject payments proposed by the parties. Repeated or serious breaches of this obligation would allow the enforcing body, proposed to be the HFEA, to use its powers to sanction the RSO. This sanction may be of limited effectiveness in parental order cases, where oversight of the RSO may be less.

Thirdly, the Report also considered the feasibility of implementing an enforcement scheme of civil penalties against the intended parents. It is proposed that intended parents could face financial penalties for making payments outside of the permitted categories, with the amount of the penalty being linked to the amount that was unlawfully paid to the surrogate. This would apply to both pathway and parental order cases, although it was acknowledged that this could operate only in relation to domestic cases, thus excluding intended parents who make payments to surrogates in international arrangements. This proposal, however, was recognised as one that may be difficult to manage (with no obvious enforcement body) and could deter intended parents from pursuing domestic arrangements. As such, the Law Commissions recommended that it be for the Government to choose whether to adopt the scheme alongside the regulatory enforcement against RSOs.

Recovery of payments

Another key recommendation that promotes the financial security of surrogates entering surrogacy arrangements is the right to recover payments. The would allow surrogates to recover agreed payments from the intended parents, which are documented on the financial annex through the civil courts. Similarly, intended parents would be able to recover costs from the surrogate for payments made and not spent on agreed costs. For arrangements made via the parental order route, recoverable payments would be those reviewed and authorised by the court.

This right to recovery would apply to all payments made or owed within the ‘protectable period’, lasting from the time the agreement was enter into until 6 weeks after birth. With the exception of life and critical illness insurance, lost payments due to illness and post-birth counselling or therapy, any payments made or promised after the protectable period would not be recoverable. For those excepted categories, there would be a long-stop of 2 years. The surrogate would not be able to recover an agreement of a gift or a recuperative holiday from the intended parents.

The Law Commissions were clear in the Report that recovery for agreed payments does not mean that the surrogacy agreement itself is enforceable: there would be an entitlement to recovery, irrespective of whether the purposes of the surrogacy agreement are fulfilled.

Commentary

The recommended payments scheme offers a clear and comprehensive guide of permitted payments for the intended parents to follow. It is clear that the Law Commissions are seeking to promote a system in which surrogates are not persuaded by financial incentives, but also ensures that they are supported and never left worse-off from acting as a surrogate. This is evident through provision for mandatory payments relating to the initial screening requirements on the new pathway, and the lack of a cap on payments for other expenses they may incur. Furthermore, the recommended approach attempts to prioritise the best interest of the child through its removal of the link between the issue of payments and the granting of a parental order.

However, the introduction of civil penalties is a contentious reform, acknowledged within the Report. It would raise particular issues in relation to the overall aim of the recommendations to encourage domestic surrogacy. With international surrogacy arrangements, which are often commercial in nature, being excluded from the enforcement scheme, it may continue to incentivise intended parents to cross-borders to engage with surrogacy in order to avoid liability.

Overall, the recommended changes are significant, and appear to strike a fair balance between the best interests of the child and protection for surrogates. There do remain concerns with the recommendations, however, that the Government would need to reflect upon when considering implementation.

Leave a reply to Regulated Surrogacy Statements: The Gateway to the Pathway – reforming surrogacy law Cancel reply