Although adoption orders following a surrogacy arrangement are not common, this is the third such reported case in a short period of time. The judgment, published in March, concerned an application for adoption of a child born of a traditional surrogacy in 2005 meaning that by the time of the hearing, the surrogate-born individual was 18 years old. The case has a complex litigious history, but the granting of the adoption order will provide certainty and security for all parties going forward.

Case background

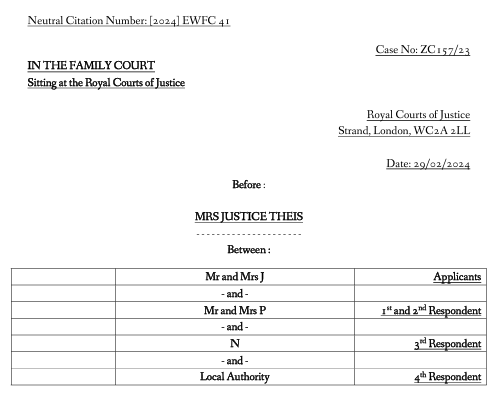

The intended parents, Mr and Mrs J, entered into a traditional surrogacy arrangement with Mrs P which resulted in the birth of the child, N, in 2005. As the woman who gave birth, Mrs P was the child’s legal mother, and because she was married, her spouse Mr P was the legal father. Mr and Mrs J had no legal connection to the child, despite the father being the genetic parent.

In this most recent judgment, Theis J recounted the litigious background to the case, which involved Mrs P lying to the intended parents about miscarrying the pregnancy and then keeping the child in her care. In the first case, Re P (Surrogacy: Residence), upon application by the intended father who had become aware of this deceit, Coleridge J ordered that N reside with the intended parents, which granted them parental responsibility. This residence order was put in place alongside contact arrangements for the child to maintain a continuing relationship with the surrogate and her husband. Although there was no finding that N was not being appropriately cared for by Mr and Mrs P, Coleridge J referred to the ‘deliberate and premeditated deceit’ by the surrogate as causing concern as to whether they would ensure continued contact for the intended parents should the child remain in their care.

This decision was appealed by Mr and Mrs P on the grounds that Coleridge J had: given insufficient weight to the effect on the child of changing his residence; overestimated the likelihood of successful continued contact between N and Mr and Mrs P given the distance and costs involved; and gave insufficient consideration to the capacity of Mr and Mrs P to parent. The appeal was dismissed by Thorpe LJ in Re N (A Child).

Accordingly, the child was moved to live with the intended parents, and a final welfare order was made in 2010 providing for indirect contact between the child and Mr and Mrs P six times a year via skype and present-giving for special occasions.

As N got older, the contact arrangements became more difficult for the child to engage with, resulting in the Skype contact ceasing in 2021. The evidence provided in the case was that there had been very limited contact since.

The adoption application

The adoption application was sought by the intended parents and supported by N and the local authority. Both Mr and Mrs P opposed the adoption application, meaning the decision for the court was whether the consent of the legal parents should be dispensed with. The basis upon which such consent can be dispensed with is where the lifelong welfare of the child demands it.

The intended parents stated that the adoption order would allow ‘N to go into his adulthood with a permanent and lifelong link to them’, given the current disparity between their lived experiences as a family and legal parental status. The child turned 16 in 2021, at which point the residence order expired.

Equally, N supported the order being granted. He spoke of the close and strong relationship with his parents and sibling, and the contrast with the difficult relationship he had with Mr and Mrs P, resulting in his decision to stop contact with them. In his view, an adoption order would be a:

big part of his life and his identity saying ‘Things don’t add up for me at the minute. I have always considered myself a J and everything says P’. He described how close he is to his brother, A, but said ‘I am not legally his brother, not feel right to me…I want to be able to legally say I am his brother for the rest of my life’. When asked about how he felt that A has a legal relationship with Mr and Mrs J, he said they always treated them equally but part of him did not feel completely part of the family. He was very clear his views were his own stating ‘I would like this to happen’. He said he hoped Mr and Mrs P would have been supportive of the application once they knew his views.

para 32

The adoption order was further supported by the Local Authority, who provided evidence that the order would:

give N the sense of belonging and equality within his family he seeks; it will create a lifelong legal connection to the people who have acted as his parents throughout the majority of his life; it is also considered it will provide a sense of closure and finality, as he enters adulthood.

para 36.

In contrast, Mr P remained opposed to the adoption order which would have the effect of severing all legal ties between himself and his wife and N. Of primary concern was that N’s behaviour towards them would change if their parental status was removed.

The outcome

Theis J granted the adoption order, dispensing with Mr and Mrs P’s consent on the basis that the child’s lifelong welfare required it. She stated that of significance were:

the strong family ties that exist between Mr and Mrs J and N. N has lived with them for the last sixteen years, he regards them as his parents and A as his brother. They are his family in every sense of the word. N is very clear he wants those important relationships to be secured in a legal and lifelong way, which an adoption order would do.

para 71.

As such, it was held that the adoption would remove the disconnect between his lived reality and legal relationships.

Whilst it was acknowledged that there would be an interference with Mr and Mrs P’s family life, such interference would be relatively low given the reduced level of contact between them and N already. In contrast, it was said that the ongoing interference with the family life for N and Mr and Mrs J was significant, with the current legal position negatively impacting on their lifelong security and stability.

Comments

By the time of the hearing, N, the surrogate-born individual was 18 years old. As stated in the judgment, the order will allow him to head into adult life with certainty and stability as to his legal status as a member of his family. However, the case exemplifies the ongoing impact that disputes following surrogacy can have: he had lived the vast majority of his childhood in a legally precarious position, whereby his primary carers had parental responsibility by way of a residence order alone, with legal parenthood vesting in individuals he had irregular contact with.

It is not specified as to why adoption proceedings were only commenced after expiry of the residence order, although the maturity of the surrogate-born individual did allow greater significance to be attached to his wishes and feelings as an aspect of the welfare assessment.

Leave a comment