Earlier this year, another reported judgment considered whether a step-parent adoption order could be granted to re-allocate legal parenthood following surrogacy. Re Z (Surrogacy: step-parent adoption) concerned an application for a step-parent adoption after an earlier decision that a parental order could not be granted. On the facts, the application was refused. This post examines the case, and reasoning for the decision, before offering some comments in light of the Law Commissions’ recommendations.

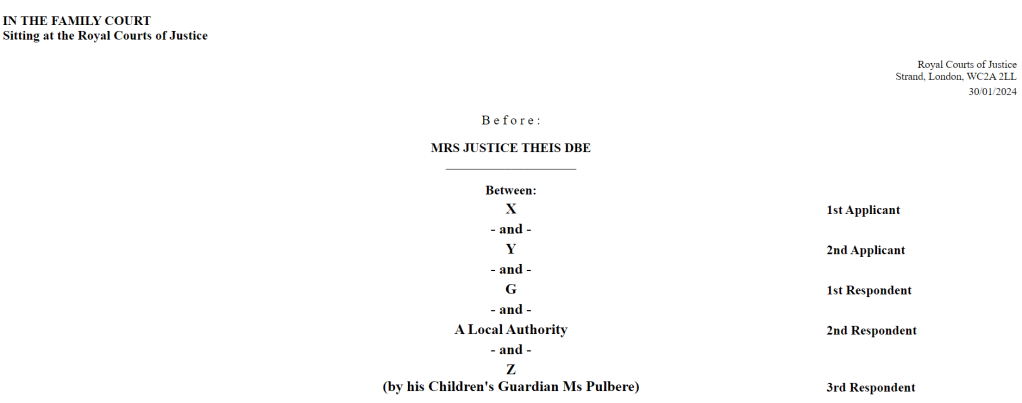

Background to the case

The background to this case concerns an earlier case, and subsequent appeal. In the appeal case, the Court of Appeal had held that a parental order could not be granted because the surrogate’s consent was not free or unconditional, as required under s54(6) Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008. This was because the surrogate had only agreed to the parental order during the proceedings on the basis that child arrangements orders (CAOs) were put in place for her to have continuing contact with the child. For a more detailed consideration of this appeal case, I have written on it in another blog.

Without the parental order, the child remained the legal child of the surrogate and the genetic intended parent. A CAO for contact between the surrogate and child remained in place. However, there were continued difficulties in the relationship between the surrogate and intended parents, resulting in disputes as to the contact arrangements.

Resultantly, this recent case concerned two applications. First, to vary the contact arrangements in place by way of a CAO, with the intended parents wanting a reduction in the number of contact visits. Secondly, an application for a step-parent adoption order. This would have the effect of removing the surrogate’s legal parenthood, recognising both intended parents as the legal parents of the child.

The legal framework

As established in the earlier Court of Appeal case, it is not possible for a parental order to be granted if the legal mother does not consent to it in a free and unconditional manner. As such, the only way for the non-genetic intended parent to be recognised as the child’s legal parent would be by way of an adoption order. Under s47 of the Adoption and Children Act 2002, each parent of the child must consent to the granting of the order, unless the court determines that such consent should be dispensed with. The ground for dispensing with consent is where the welfare of the child demands it. The welfare checklist contained within s1(4) of the Act requires the court to consider the child’s ascertainable wishes and feelings, the needs of the child, the effect of the change upon the child, the child’s relationships with their relatives and any harm the child may suffer.

As regards the variation of the contact arrangements provided for in the CAO, any such variation would need to be in the child’s best interests, using the welfare checklist in s1(3) of the Children Act 1989. The welfare considerations in the Children Act and Adoption and Children Act are substantively the same.

The decision

Theis J, hearing the case, acknowledged the length of the judgment. This was due to the complexity of the background, as well as the detailed reports of the experts in the case. The experts in this case were divided in their opinion as to what the best outcome would be.

On the one hand, the jointly-instructed clinical psychologist was of the view that the existing provisions of the CAO should remain in place, enabling a meaningful relationship between the child and surrogate. As for the step-parent adoption order, he was of the view that it was not necessary to dispense with the surrogate’s consent on a welfare basis because all parties were in agreement as to the fact that the child should live with the intended parents. As such, he did not perceive there as being an overwhelming welfare need for the adoption order to be granted.

Contrastingly, the Local Authority reporter and Child’s Guardian supported a reduction in the contact arrangements provided for in the CAO based on the need to strike the correct balance the child’s family life with his intended parents and need to know the surrogate as a part of his identity. They were also of the opinion that the step-parent adoption order should be granted, to provide ‘lifelong security and stability’ to the child as being a part of his family.

Ultimately, Theis J accepted the evidence of the clinical psychologist in relation to the step-parent adoption order. In her view, such an order was not needed because all parties were in agreement that the child should continue living with the intended parents. By granting a ‘lives with’ CAO in favour of the non-genetic intended parent, he would be able to exercise parental responsibility in a meaningful way and the family unit would remain intact. Therefore, the child’s welfare did not demand the surrogate’s consent to be dispensed with. The fact that a lives with CAO exists only until the child is 16 years old was acknowledged, but it was deemed appropriate on the facts.

As regards the contact arrangements, it was ordered that the surrogate have direct contact with the child 4 times a year, deemed sufficient to maintain a meaningful relationship without interfering too much with the child’s day-to-day family life, with additional indirect contact opportunities. Given the intended parents’ hesitancy to contact previously, Theis J spoke of her concerns as to the effect of an adoption order on continued contact between the child and surrogate:

I consider when the spotlight of the court is turned away there are real risks that they will not comply with orders of the court due to their inability to properly recognise and understand the welfare need for Z to have a meaningful continuing relationship with G and why. I consider that risk is likely to be higher if there is an adoption order, as it is likely to be viewed by them as a way of further securing their legal relationship with Z at the expense of Z’s welfare due to the obstacles they are likely to put in the way of that meaningful relationship between Z and G being maintained and supported.

para 241.

Therefore, the surrogate remains the legal parent of the child but with very limited ability to exercise parental responsibility. The non-genetic intended father will have parental responsibility over the child until he reaches 16 years old. The child will be entitled to direct contact with the surrogate four times a year.

Comments

As Theis J stated, this case demonstrated the difficulties that can arise when surrogacy arrangements do not go as intended:

Whilst many surrogacy arrangements work very successfully, this case provides a graphic illustration of the difficulties that can be encountered if the arrangement breaks down. The need for caution, proper preparation, support and understanding before entering into a surrogacy arrangement is clearly advisable for very good reasons.

para 205.

In her view, the implications of the surrogacy arrangement for all parties had not been fully considered prior to the pregnancy, including the decision for the surrogate to use her own gametes after a failed attempt using donor eggs.

Whilst disputes following surrogacy are rare, these judgments demonstrate the impact that it can have on all parties to the arrangement – and most significantly, the child.

The Law Commissions’ recommendations for reform emphasise the importance of having proper pre-conception checks and safeguards in place. Such processes will be a prerequisite to the arrangement proceeding on the new pathway, and can be hoped to minimise conflict and disputes following a surrogacy arrangement. However, it must be anticipated that disputes will continue.

Even with the new recommendations in place, the outcome in this case would likely have been the same: the surrogate would have been entitled to withdraw her consent on the pathway, resorting to a parental order determination. Based on the earlier appeal case and this decision, decided on the basis of the child’s welfare and best interests, it is unlikely that the judicial determination would have been any different.

Leave a comment