International legal compliance requires the UK to fulfil its obligations and responsibilities as outlined in international agreements, treaties, and conventions. This commitment involves aligning domestic laws and policies with international standards and implementing international agreements. The UK’s legal system follows a dualist approach, thus international law does not automatically become part of domestic law unless it is explicitly incorporated through parliamentary authority. This authority is granted through Acts of Parliament or secondary legislation.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has clarified that relevant provisions from international conventions, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), should inform the interpretation of rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which is incorporated into UK domestic law through the Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998. As a result, any new law should be passed with these rights in mind.

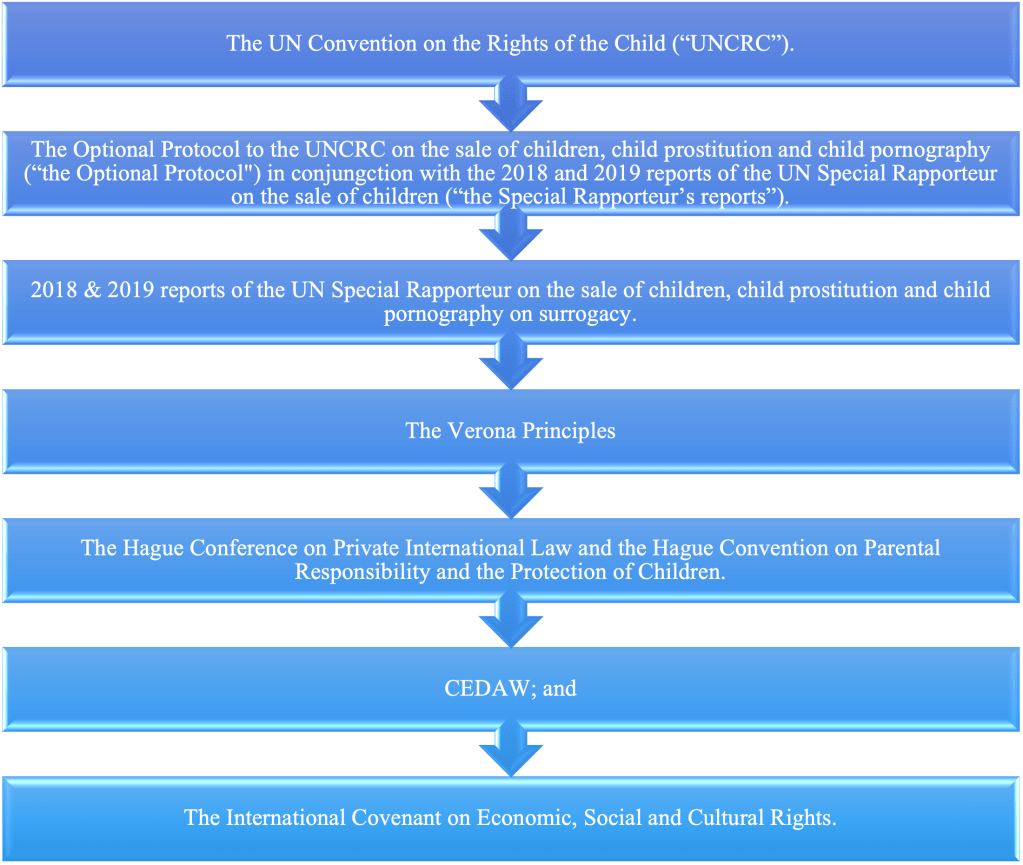

The Law Commissions, within their Final Report, highlighted some key international obligations which relate to surrogacy law reform, shown in the diagram below:

This blog will focus primarily on the UNCRC, The Optional Protocol and the Special Rapporteur Reports, and The Verona Principles, as they are the most relevant and analysed in the Final Report. However, other important international framework and obligations were considered by the Law Commissions, such as:

- The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).

- The Hague Conference on Private International Law and the Hague Convention on Parental Responsibility and the Protection of Children.

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

The Law Commissions acknowledged that CEDAW describes pregnancy as a ‘social function’ meaning that payment for such a pregnancy could be incompatible with it’s terms. In terms of the recommendations, it was recognised that any provision for permitted payments could invoke this Convention: however, as the Final Report discourages commercial surrogacy throughout the reform recommendations, the Law Commissions viewed the permitted payments regime as CEDAW compliant.

Moreover, currently there is no international regulation of surrogacy arrangements. The Hague Conference on Private International Law and the Hague Convention on Parental Responsibility and the Protection of Children have been working on addressing the issues related to international surrogacy, trying to find a compromise between different countries positions. As far back as 2014, the Conference acknowledged the challenges in finding a consensus due to varying approaches to legal parentage and the complex public policy considerations involved. Nonetheless, the 2022 Report recommended that further work take place to try to reach agreement on how States recognise parentage established following surrogacy internationally.

UNCRC (the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child)

The UNCRC is an international treaty establishing the rights of children globally by defining the minimum standards for their care and development. The UNCRC outlines the obligations of states parties to respect, protect, and fulfil these rights, and it provides a framework for governments to develop policies and legislation that prioritise the best interests of children. The UNCRC has been ratified by almost all countries in the world, making it the most widely accepted human rights treaty in history.

The UNCRC, along with the Optional Protocol on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography (the Optional Protocol), have been ratified by the UK. However, neither have been incorporated into domestic law. Therefore, individuals cannot directly enforce these rights in domestic courts. On this basis, the rights under the UNCRC, as Lord Justice Thorpe noted –

‘May not have the force of law, but, as international treaties, they command and receive our respect.’

Re P (A Minor) (Residence Order: Child’s welfare) [2000] Fam 15, 42

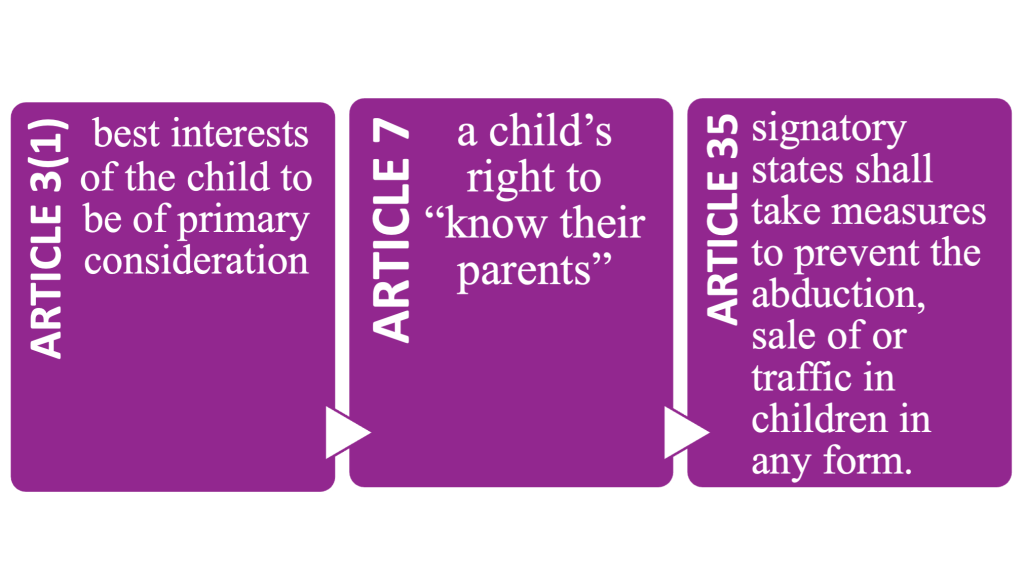

The relevant articles within the UNCRC are:

Article 3(1): best interests of the child

Article 3(1) provides that:

In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.

The Law Commissions have consistently reiterated throughout the project how their recommendations advance, protect, and focus on the rights of the child. To illustrate this, the Law Commissions specifically outlined compliance with Article 3(1) in their Final Report.

The Law Commissions are of the view that the following reform recommendations place the child’s best interests as the primary consideration:

- First, if a surrogate withdraws her consent to the agreement and the intended parents make an application under section 8 of the Children Act 1989 or section 11 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995, the court are to decide with whom the child should live and have contact – this statute directly requires the welfare of the child be the paramount consideration, wording that is deemed analogous to the best interests standard contained with the UNCRC.

- If withdrawal of consent leads to a parental order application, the court’s paramount consideration in deciding whether to make the parental order would be the child’s lifelong welfare, as is currently the case. Again, this standard is seen to equate to the best interests test, and the court tend to refer to ‘welfare’ and ‘best interests’ interchangeably.

- The Law Commissions take the view that it is in the child’s best interest for legal parental status to remain with the intended parents if the surrogate withdraws her consent after birth, as this will provide more clarity and stability for the child’s lived reality and protection of their origins. However, this will operate on a case-by-case basis.

Article 7: a child’s right to ‘know their parents’

Article 7 provides that:

The child shall be registered immediately after birth and shall have the right from birth to a name, the right to acquire a nationality and. as far as possible, the right to know and be cared for by his or her parents.

The UNCRC does not define a ‘parent’, so it cannot be assumed that this refers to solely a birth or gestational parent. For surrogacy, the Law Commissions interpreted ‘parent’ broadly, to cover both gestational and intended parents.

Article 7 is often asserted as establishing the right to ‘know’ both gestational and genetic parents. Interestingly, the Final Report refers only to the right of the child to know the identity of the surrogate and intended parents, with little reference to the right to know genetic parents (albeit that this is dealt with later in their recommendations in relation to the Surrogacy Register). From this interpretation of Article 7, the Law Commissions assert that the recommendations satisfy the right to know through the introduction of the Surrogacy Register on the new pathway. As discussed in further detail in an earlier post, the Surrogacy Register is expected to contain identifying information about the surrogate and the intended parents, thus providing the surrogate-born child with the relevant information relating to the nature of their conception and birth.

Additionally, the Law Commissions recommend that a child should have full access to their parental order court file when they reach the correct age (16 (Scotland) or 18 (England and Wales)), or younger if they have the requisite level of competence or capacity, on the basis that it will provide a curious child with the relevant information required by Article 7.

Beyond the right to ‘know’, Article 7 also refers to the right of the child to have an ongoing relationship with – that is to ‘be cared for’ by – the parents. In relation to this, the Law Commissions outline that no surrogate may be forced into an ongoing relationship with the child. However, if a surrogate does still want to remain in contact with the intended parents and the child, this is obviously permitted. To aid this, the Law Commissions specify how Regulated Surrogacy Organisations (RSO) would need to encourage parties to make a clear statement in the Regulated Surrogacy Statement (RSS) on the expectations of ongoing contact.

Optional Protocol Article 35: Prevention against sale, abduction, or trafficking:

UNCRC Article 35 –

States Parties shall take all appropriate national, bilateral and multilateral measures to prevent the abduction of, the sale of or traffic in children for any purpose or in any form.

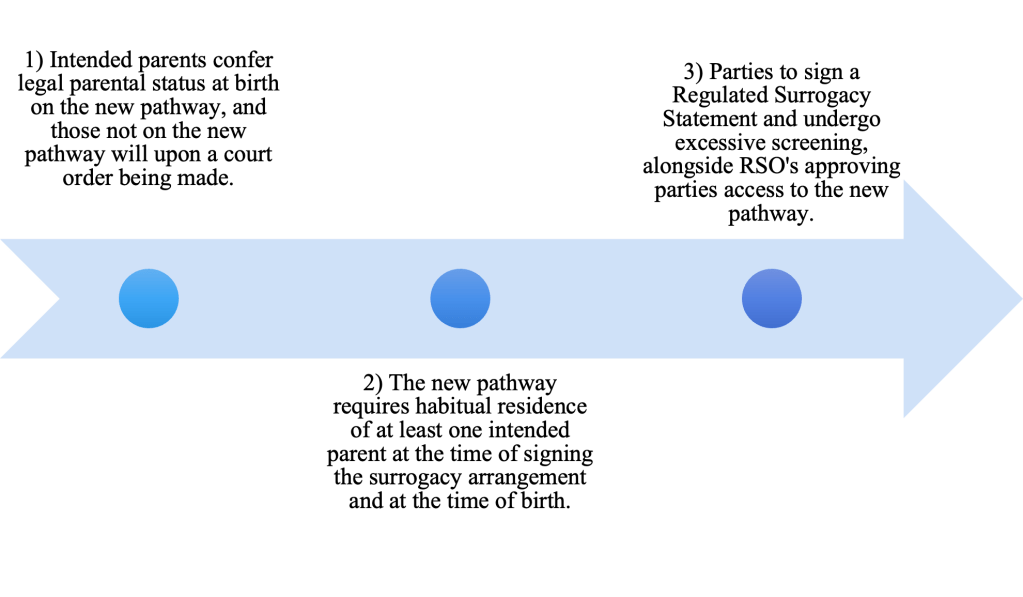

A consistent theme throughout the Consultation Paper and Final Report is the Law Commissions aim to provide sufficient safeguards against the risks of sale or trafficking of both children and surrogates. The Law Commissions advance their compliance with Article 35 through the following recommendations:

The Law Commissions assert within the Final Report that the requirement of habitual residence:

‘…will help prevent women being exploited by being brought to the UK simply for the purpose of being a surrogate on the new pathway.’

Further, surrogates and intended parents on the new pathway will have to sign a RSS and undergo extensive screening and checks, including relating to health and criminal background. Additionally, any agreements must be approved to access the new pathway by the RSO. Therefore, there is written proof of the agreement between the parties, consistent oversight by RSOs, and screening which will all aid in the prevention of any potential sale, abduction or trafficking.

The Law Commissions go further by suggesting that if intent to traffic a child is flagged, these people will not be accepted onto the new pathway. This assertion holds true due to the regulation and oversight provided by the RSO to ensure that all parties involved are suitable for surrogacy. The measures and safeguards implemented on the new pathway significantly reduce the risk of child trafficking, providing a strong argument for the effectiveness of the Law Commission’s recommendation.

The Optional Protocol and the Special Rapporteur’s Report

Article 1 of the Optional Protocol prohibits the sale of children.

Article 2(a) defines the sale of children as:

‘Any act or transaction whereby a child is transferred by any person or group of persons to another for remuneration or any other consideration.’

In a 2019 Report, the Special Rapporteur on the sale and sexual exploitation of children suggested that the Optional Protocol’s definition of the sale of children has three components:

- remuneration or any other consideration, that is payment;

- transfer of a child; and

- the exchange of payment for the transfer of a child.

The Special Rapporteur recommended that courts or competent authorities require reasonable and itemised reimbursements to surrogates in altruistic arrangements, to ensure there are no disguised payments for the transfer of the child.

The Law Commissions have consistently emphasised that the recommendations do not permit commercial surrogacy, instead keeping arrangements altruistic with the absence of payment for gestational services or for the handing over of the child.

Further, the Special Rapporteur’s view is that to protect against the sale of a child, the surrogate should always be the child’s legal parent at birth. In this regard, the Law Commissions proposed new pathway would not, on the face of it, accord with the Optional Protocol. Under the new pathway, if the surrogate’s consent has not been withdrawn, the intended parents will become the child’s legal parents at birth. However, the Law Commissions argue that this approach does not constitute the sale of children for the following two reasons:

- No child is being transferred for payment within the regulated altruistic framework. Payments are strictly limit to cover the surrogate’s costs, such as travel and lost earnings, without allowing profit or compensatory payments. The permitted payments have been discussed further in a previous post.

- Surrogates would be required to undergo implications counselling to address their motivations and ensure they are not at risk of exploitation.

Consequently, the Law Commissions are confident that intended parents obtaining legal parenthood at birth through the new pathway would not involve the transfer of a child in exchange for payment.

The Verona Principles: Principles for the protection of child born through surrogacy

The Special Rapporteur explicitly supports the Verona Principles. The Principles provide that if the surrogate either revokes consent or fails to confirm consent, a court or competent authority should conduct a best interest of the child assessment, considering a psycho-social evaluation of all parties involved. This aligns with the recommended process in cases where the surrogate withdraws consent to proceed with the new pathway. However, the Verona Principles do not specifically address the issue of legal parental status for the child if the surrogate revokes consent before birth.

Concluding comments

The Law Commissions’ proposals aim to ensure compliance with international obligations, particularly those contained in the UNCRC. The recommendations prioritise the best interests of the child by providing advanced protection in cases where a surrogate withdraws consent, emphasising the child’s right to know their parents through the establishment of a surrogacy register and access to parental order court files, and implementing safeguards against the risks of child sale, abduction, or trafficking.

While some inconsistencies exist, overall, the Law Commissions’ recommendations seem to align with international standards. By addressing these issues, the UK demonstrates its commitment to upholding the rights of children born following surrogacy arrangements.

Leave a comment