Following initial posts providing an overview of the Law Commissions Final Report, it is necessary to explore some of the contentious aspects of surrogacy arrangements and the impact of the suggested reforms. Surrogacy may invoke political and ethical debate relating to, for example the exploitation of women and how to balance and promote women’s rights and the welfare of the child alongside medical advancements.

This blog will focus on the surrogates right to withdraw consent. Specifically, analysis will focus on whether the Law Commissions recommendations strike a fair balance between the rights and interests of each party – the surrogate in retaining her autonomy, and the intended parents, in having their intention realised.

The importance of a surrogates ‘ongoing’ and ‘free’ consent has been recognised in both the seminal case of Re C (Surrogacy: Consent) and the Law Commissions throughout the Consultation Paper and Final Report. The Law Commissions reiterate that their reform proposals are intended to serve the best interests of all parties, and have retained throughout the process of the project that a surrogates right to withdraw consent is pivotal to surrogacy.

It is clear throughout the reform proposals that the Law Commissions intend to safeguard the surrogate, to hopefully minimise her desire to withdraw consent, through the implementation of pre-conception checks and advice. Nonetheless, there may remain circumstances where a surrogate does wish to withdraw her consent to the surrogacy arrangement, either before or after the birth of the child, and the recommendations detail the process that would follow in such an eventuality.

The primacy of consent

Currently, surrogacy arrangements are unenforceable. This means that surrogates can refuse to hand over the care of the child to the intended parents, and their refusal of consent to the granting of a parental order cannot be overridden by the court.

Surrogates may change their minds about the arrangement for a variety of reasons, such as a deterioration of the relationship between themselves and the intended parents, or acquiring an emotional attachment to the child. It must be noted, however, that instances where a surrogate changes her mind in relation to the intended parents taking care of the child are very uncommon.

Nonetheless, reducing the role of gestation and the process of childbirth to a mere bodily function would undermine the nature of pregnancy, and would overlook the psychological and physical effects of birth on a woman. Therefore, the primacy of consent from the surrogate within the legal framework can be understood. However, if the aim of potential reform in the law on surrogacy is to enhance certainty for the parties to the arrangement, any retention of the ability for consent to be withdrawn could be criticised on the basis of continuing uncertainty.

The current law: parental orders and consent

Under the current legal framework, a surrogate must consent to the granting of a parental order, as provided for by s54(6) Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008. As outlined in an earlier post, a parental order is a post-birth court order that transfers legal parenthood from the surrogate (and her spouse, if applicable) to the intended parents. Upon the grant of a parental order, a new birth certificate is issued reflecting the intended parents’ status as legal parents, and extinguishing the surrogate’s legal responsibilities over the child.

Consequently, intended parents could find themselves in an ambiguous legal position if the surrogate refuses to consent, as they are unable to become the legal parents even if they have care of the child. In such cases, the courts are likely to (and have) granted child arrangements order providing parental responsibility to allow the intended parents to continue caring for the child who is living with them. This is, however, far from ideal in that the child’s lived reality would not be reflected in their legal parentage.

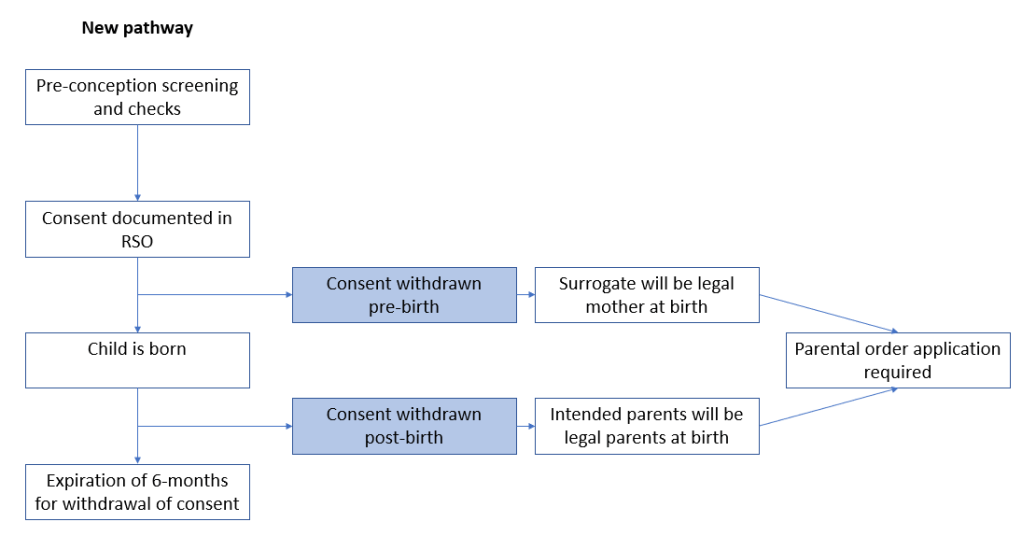

Under the recommendations for reform in the Law Commissions Final Report, they have proposed two paths to parenthood: the new pathway, and a revised parental order process for cases not eligible for the pathway. In both instances, the surrogate’s consent remains an important aspect of legal parenthood being allocated to the intended parents.

Consent on the new pathway

Under the recommended new pathway, the intended parents would be the child’s legal parents from birth, provided that the surrogate has not withdrawn her consent to the arrangement.

The implication of a surrogate withdrawing her consent would depend upon whether it occurred before or after the birth of the child.

If the surrogate withdrew consent before birth, the arrangement would no longer proceed on the pathway. This means that the surrogate would be the legal parent from birth, and the intended parents would need to pursue a parental order to obtain legal parenthood.

If the surrogate withdrew her consent after birth, but within six months, the intended parents would still be the legal parents – as this is allocated at birth – and the surrogate would need to apply for a parental order to recognise her as the child’s legal parent.

Unlike the current s54 criteria, the Law Commissions recommend that the requirement for the surrogate’s consent in parental order cases be able to be dispensed with, where the child’s welfare demands it. Therefore, in contrast to the current situation, the court could grant a parental order in favour of the intended parents even without the surrogate’s consent.

In such circumstances, the court must decide which party acquires parental status and parental responsibility based on all relevant circumstances and in accordance with the lifelong welfare of the child. This appears to be the only fair approach, and considers the surrogates wishes amongst the facts of the arrangement.

Attempts to ensure continued consent on the new pathway

In order to try to minimise the potential for disputes, and the withdrawal of consent by the surrogate, the Law Commissions’ Final Report makes recommendations that operate as safeguards to both parties and help to promote the surrogates’ rights.

Written surrogacy arrangements:

On the new pathway, the Law Commissions intend to establish the exact intention of the parties involved through a written surrogacy arrangement, referred throughout the Report as a Regulated Surrogacy Statement (RSS). Parties should seek legal advice and obtain support from a Regulated Surrogacy Organisation (RSO) to draft the RSS. Although not enforceable, the RSS will document all parties’ intentions, and should ensure they feel a level of security in the documentation of that intention.

Age imposition for a surrogate:

Moreover, the Law Commissions have recommended more stringent requirements on who may act as a surrogate. Specifically, they recommend that women should only act as a surrogate if they are over 21 years old. Other requirements were consulted on, including the requirement to have had a child previously and to limit the number of surrogacy pregnancies that an individual can undertaken, but the Law Commissions concluded that these would restrict a woman’s autonomy too much. Further, such factors could be taken into account, if needed, in the pre-conception screening process.

By limiting the age that a woman can act as a surrogate to 21 years old, the Law Commissions hope to minimise any exploitation of vulnerability due to age, and were of the view that it would allow further emotional and physical maturity. It would therefore be hoped that this would counter some of the risks of a withdrawal of consent where the surrogate was perhaps not emotionally prepared to act in such a role.

Would the reforms be effective?

While some may argue that these reforms weaken the legal position of the surrogate, in allowing the court to grant a parental order absent the surrogate’s consent, it is important to recognise that the intention behind the recommended changes is to provide legal certainty and to meet the best interests of the child.

The reforms aim to promote the surrogates autonomy by viewing her consent as a continuing action, which, if withdrawn at any point, would remove the arrangement from the pathway. However, one must consider the extent to which the proposed reforms do, in fact, maintain the primacy of consent.

Although the surrogate does have the option to withdraw her consent, realistically in most cases the court will decide in favour of the intended parents given that the child is usually already in their care. It would be difficult to imagine a situation where it would be in the best interests of the child to deny the intended parents legal parenthood where their lived reality is with those parents. Under the current legal framework, whilst parental orders cannot be granted without consent, the court have still made alternative arrangements providing for the intended parents to have parental responsibility and appropriate orders in place to allow them to live with, and care for, the child.

Therefore, a surrogate’s emotional attachment to a child, or alternative reasoning for withdrawal of consent, is unlikely to persuade the court to grant her legal parenthood unless the surrogate can establish a further connection with the child – for example, in instances where the intended parents never took over care for the child. However, in cases where the child is living with the intended parents and the surrogate withdraws her consent post-birth, it is difficult to see a scenario in which the surrogate would succeed, as it is not likely to accord with the best interests of the child.

Comments:

In conclusion, the Law Commission’s Final Report presents a nuanced approach to balancing the rights and interests of all parties involved. Whilst aiming to provide legal certainty and stability for intended parents, they also recognise the importance of a surrogate’s ongoing and free consent.

The implementation of written surrogacy arrangements on the new pathway serves as a safeguard for intended parents, offering a level of security in having intention clearly documented. Additionally, the introduction of a more stringent age requirements for the surrogate aims to minimise the risk of a surrogate changing her mind due to a lack of preparedness for the implications of pregnancy and a surrogacy arrangement.

However, whilst the reforms intend to promote the surrogate’s right to withdraw consent, in practice, the court tends to rule in favour of the intended parents, as demonstrated in previous cases. Further, the ability to dispense with the surrogate’s consent under the revised parental order pathway would in fact undermine the current primacy given to consent. Thus, the extent to which the proposed reforms fully align with the Law Commissions’ emphasis on allowing the surrogate to act according to her wishes remains an area of debate. It is imperative to strike a balance that ensures the welfare of the child, respects the autonomy of the surrogate, and provides certainty for all parties involved: this is not an easy balance, and there remain concerns over whether it has been struck correctly in the proposed reforms.

Leave a comment