Opting for the UK as a surrogacy destination does not appear to be a common route for foreign intended parents. This may be due to the non-commercial nature of surrogacy in the UK as well as a perceived shortage of available surrogates. Nonetheless, the Law Commissions have expressed concern about any changes in the law encouraging ‘surrogacy tourism’ to the UK, and have thus made recommendations to better regulate the process for foreign intended parents to remove surrogate-born children from the jurisdiction. In their Final Report, it has been recommended that the court should approve of the removal of the child if they consider it within their best interests, amongst other recommendations.

Current law

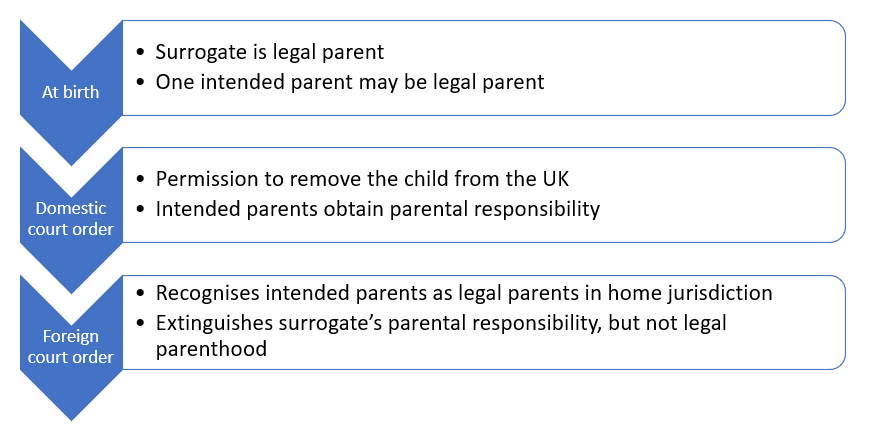

Under the current legal framework, the surrogate is the legal mother of any child that is born. Foreign intended parents generally will not meet the criteria for the grant of a parental order because they are not domiciled in the UK, as required under s54 of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008. Therefore, they would need to return to their home country in order to establish legal parenthood. However, at the point of removing the child from the UK, the intended parents would not be the legal parents of the child.

Removing the child from the jurisdiction to return to their home country necessitates involvement of the surrogate. The surrogate, as the legal mother, would need to travel with the intended parents and the child, or she can give written authorisation for the intended parents to remove the child from the jurisdiction.

The issue is that there are no other restrictions for intended parents to remove the child from the UK for this purpose. This raise concerns over whether there is adequate protection of the welfare of the surrogate-born children, and how easily children may slip through the net and be susceptible to human trafficking, issues recognised by the Law Commissions in their Final Report. A comparison of the present system for cross-border surrogacy with international adoption highlights the shortcomings of the present process.

Provisional Proposals in the Consultation Paper: aligning the process with international adoption

Within the 2019 Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions recognised the enhanced protections for children involved in international adoption in comparison to surrogate-born children. Most importantly, for an intended parent to remove the child from UK for the purpose of adoption, they must be granted permission by the court. This provides a significant protection against the concerns expressed above, such as the child’s welfare and trafficking.

The relevant legislation governing the removing a child for the purpose of adoption, s84 Adoption and Children Act 2004 (and s60 of the Adoption and Children (Scotland) Act 2007, states that it is a criminal offence to remove the child unless the adoptive parents have obtained an order from the court granting permission to the removal. An order granted by the court acts like an adoption order, conferring parental responsibility of the child to the adoptive parents and removing the parental responsibility of any other persons. When granting this order, the child’s lifelong welfare must be the paramount consideration, and the requirements established by The Adoptions with a Foreign Elements Regulations 2005 (the 2005 Regulations) must be satisfied.

The 2005 Regulations place obligations on both the UK adoption agency and the relevant foreign authority to prevent adoptive parents from circumventing the requirements of UK adoption law. The domestic adoption agency and relevant foreign authority must be satisfied, amongst other safeguards, that the adopters have been assessed for suitability and that the child is recommended for adoption.

These provisions for international adoption highlight the shortcomings of the current system relating to cross-border surrogacy, whilst also offering a potential framework for how such a system could operate in a surrogacy context.

These provisions can be, and have previously been, utilised in a surrogacy context. In Re G (surrogacy: Foreign Domicile) an order was made under s84 of the ACA 2002 to allow Turkish intended parents to remove the child from the UK. As they were not domiciled in the UK, and thus not eligible for a parental order, the only way for them to acquire legal parenthood of the child was to remove them from the UK for adoption in their home country, via s84. However, s84 can only apply following a surrogacy arrangement where the only way for intended parents to become the legal parents of the child in their home country is through adoption. Therefore, if there is an equivalent to a parental order available in their home country, s84 would not be applicable, and there would not be equivalent protections.

Within the Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions recognised this as an area in need of reform. They considered whether in cases where foreign intended parents apply for the equivalent of a parental order in their home country, there should be restrictions on the removal of the surrogate-born child for this purpose. Notably, the Law Commissions acknowledged that there could not be an exact equivalent procedure for surrogacy as exists for adoption because the infrastructure relied on in an adoption order, such as the adoption agency, does not exist for surrogacy.

Resultantly, the Law Commissions requested consultees views on two key issues:

- If there are any restrictions necessary on the removal of a child from the UK for the purpose of a parental order, or equivalent, in another jurisdiction;

- If restrictions are deemed as necessary, whether there should be a process allowing foreign intended parents to remove the child from the jurisdiction with court approval and, if so, what that process would entail.

Within the Consultation paper, these recommendations were regarded as important to protect the child’s best interests, and to shield against trafficking. Further, the Law Commissions were of the view that this would deter people from utilising the UK as a ‘surrogacy destination’. Overall, the Law Commissions proposed that there was a ‘strong case’ for reform of this area.

Recommendations in the Final Report: An order to remove the child from the jurisdiction

In the Final Report, the Law Commissions affirmed their view from the Consultation Paper that the only practical restriction would be to implement a requirement for foreign intended parents to apply to the courts for authorisation to remove the child from the UK for the purpose of obtaining a parental order, or equivalent, overseas.

Such a court order would therefore act as an equivalent for a surrogacy arrangement as to existing provisions that regulate a child’s removal to another country for international adoption. Moreover, the Law Commissions have mirrored the standard of consideration required by the court prior to making an order, by suggesting that court’s paramount consideration should be the child’s lifelong welfare.

However, the Law Commissions were clear on differentiating international adoption and international surrogacy legislation, with the recommendations not fully mirroring the adoption process. Instead of the adoption agency, who present evidence to the court ahead of a s84 order, it is recommended that the process would involve a Parental Order Reporter (in England and Wales) or Curator/Reporter (Scotland).

The role of the Parental Order Reporter would be to produce a post-birth report, similar to that required for a parental order, but with the exception of not needing to report on the requirement for the intended parents to be domiciled in the UK. The Law Commissions recommend that this would be best implemented through court procedural rules, in-line with the current approach.

Due to a potential lack of infrastructure in other jurisdictions, there are no recommendations for the involvement of a specified foreign authority, as is the case with adoption, although they may request further evidence, in excess of those required for a parental order, from the intended parent’s home country (such as criminal record checks).

Therefore, when determining whether to grant an order allowing foreign intended parents to remove the child from the UK in order to obtain a parental order, or equivalent, in the intended parents home country, the court’s approach would largely mirror the parental order process. The same requirements would need to be satisfied as for a parental order, with the exception of the intended parent’s link to the UK either through domicile or habitual residence.

Parental responsibility following a court order permitting removal from the UK

S84 of the ACA 2002 (or s9 of the AC(S)A 2007), as discussed above, confers parental responsibility on the prospective adoptive parents, ensuring a relationship between parent and child prior to removal from the UK.

By applying this same process for foreign intended parents who want to remove the child from the UK for the purpose of applying for the equivalent of a parental order in their home jurisdiction, it would remove the need for the surrogate to travel with the intended parents back to their home country, or for her to provide her explicit consent for them to do so. It would also ensure that the intended parents can exercise important decisions relating to the child, such as medical treatment, without requiring the surrogate’s consent.

The Law Commissions also considered whether the surrogate’s parental responsibility should be removed upon the granting of a court order permitting removal from the UK. However, they ultimately recommended that the surrogate should retain parental responsibility, in addition to the intended parents. Consultees, including NGA Law and Brilliant Beginnings, reported that foreign intended parents tend to be dissuaded from pursuing surrogacy in the UK due to the fact that the surrogate’s legal parental status cannot be extinguished in UK law. Therefore, retaining the surrogate’s legal status as mother, along with her parental responsibility, will likely continue to act as a deterrent for foreign intended parents.

This status of the surrogate as holding parental responsibility would then be extinguished by the later making of the foreign parental order, or its equivalent.

Final comments

The potential for the UK to be seen as a surrogacy destination for international arrangements raises important legal and ethical considerations. The Law Commissions’ recommended reforms aim to rectify the existing disparities between surrogacy and adoption legislation, focusing on the child’s welfare and discouraging surrogacy tourism. By establishing comprehensive guidelines and safeguards, the UK can strengthen its position as a responsible destination for surrogacy whilst protecting the rights and well-being of surrogate-born children. It will be interesting to see whether the government agree and will implement these enhanced protections. Nevertheless, the extent to which such provisions would be utilised can be debated, given the evidence that cross-border arrangements into the UK are very low in prevalence.

Leave a comment