As outlined in an earlier post, the bulk of the recommendations made in the Final Report do not apply to international arrangements, thus meaning that intended parents who engage with surrogacy in another jurisdiction will have to continue to follow the parental order process in order to have their legal parenthood established.

However, aside from establishing legal parenthood, there is a more immediate concern facing families who engage with international surrogacy: getting the child into the UK from their country of birth. Consultees reported that the process can be stressful, bureaucratic and lengthy. The sooner the child can enter the UK, the sooner the family unit can get settled within their home environment and a parental order be sought. It is therefore in the interests of all parties for this process to be reviewed. As such, the Law Commissions have made recommendations to try to streamline and ease the process.

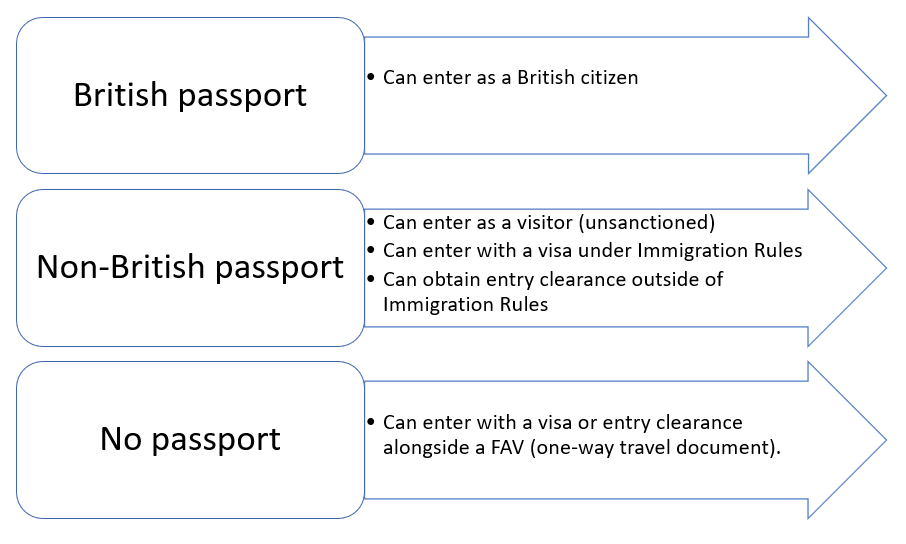

There are multiple ways in which a child born following a surrogacy arrangement can enter the UK with the intended parents.

- First, the child can obtain a British passport. A British passport can be issued if they are a British citizen. Such citizenship can be established at birth (provided the conditions are met) or via a Certificate of Registration.

- Second, if the child does not have a British passport, and the country of birth does not require a visa for entry into the UK, the child can enter as a visitor with a passport issued by the country of birth.

- Third, if the child does not have a British passport (or any passport) and the country of birth does require a visa for entry into the UK, a visa or entry clearance would need to be sought.

The Law Commissions have made recommendations to the operational aspects of each of these entry routes. This post will detail the current process and recommendations in turn.

Establishing citizenship to obtain a British passport

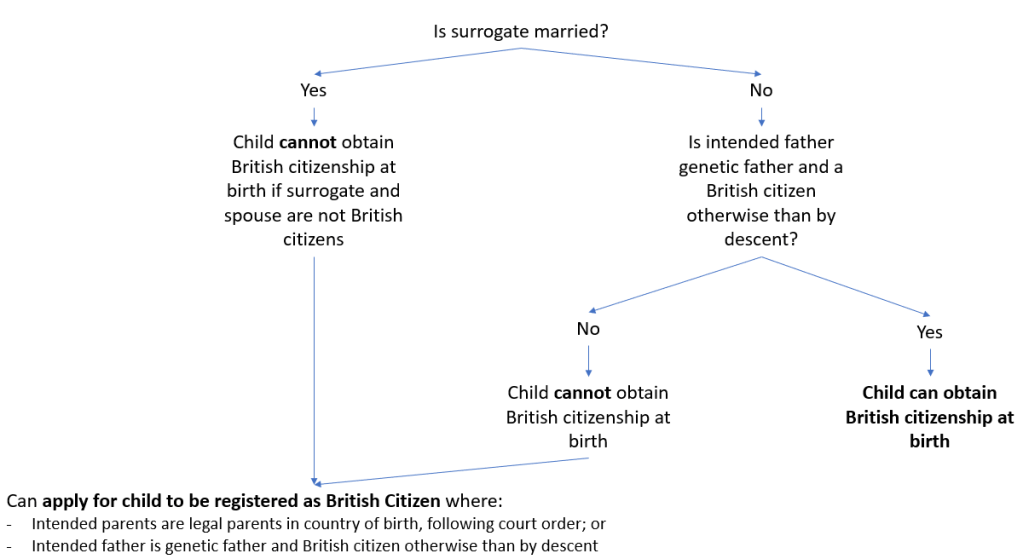

Citizenship is determined at birth, on the basis of either parent being a British citizen. As the surrogate is the legal mother from birth, and the surrogate’s spouse the legal father, in international arrangements it is unlikely that the child will obtain British citizenship at birth as a result of neither legal parent being a British citizen. If the surrogate is unmarried, however, and the intended father is the genetic father, he is a legal parent and the child can obtain citizenship from him provided that he is a British citizen otherwise than by descent (meaning he must have obtained his citizenship by birth, adoption, registration or naturalisation in the UK).

Therefore, a surrogate-born child in an international arrangement will be a British citizen at birth provided that the surrogate is unmarried and the intended father is the genetic father and a British citizen.

In all other cases – for example, where the surrogate is married, or the intended father is not the genetic father – the child will not be a British citizen at birth. Upon a parental order being granted, the child would acquire citizenship. However, the child needs to be in the UK in order for a parental order application to be made, so there need to be other mechanisms for the child to enter the UK.

The other way to establish citizenship is through applying for a Certificate of Registration from the UK Visa and Immigration Service. This Certificate can be granted at the discretion of the Secretary of State for the Home Office, and guidelines provide that citizenship can be granted where:

- the child’s country of birth has recognised the intended parents as the legal parents through a court order, with consent from all parties who would hold parental responsibility. This court order must take have been made post-birth.

- The intended father is the genetic father and a British citizen otherwise than by descent.

The recommendations

- In order to speed up the process, it is recommended that a file should be able to be opened with the Passport Office and Visa and Immigration Service prior to the child’s birth to allow the intended parents to start collating the evidence that would be required for the application. The application would not, however, be able to be submitted until after the child’s birth. Such a recommendation is a procedural matter and would not require any change in the law.

- To avoid duplication, it is recommended that the Home Office provide clear guidance on what documentation is required in the application. Again, this recommendation is operational and would not require any legal changes.

- At present, the Home Office requires a post-birth court order to issue a Certificate of Registration. This can pose an issue in relation to jurisdictions (such as Ukraine and California) that recognise intended parents as legal parents at birth, thus meaning there is no court order. The Law Commissions have recommended that the Home Office review its approach to this.

- In line with recommendations to domestic surrogacy, the Law Commissions recommend that the nationality rules be updated so that the surrogate’s spouse is not a legal father who can confer nationality to the child. This will then make it easier for intended parents who engage with a married surrogate for the child to be a British citizen at birth, where the intended father is the genetic father.

Obtaining a visa or entry clearance without a British passport

As stated above, although it is not strictly sanctioned, it is possible for a child to enter the country as a visitor with a passport issued in the country of birth where a visa is not required. Consultee responses indicate that this a commonly used method of entering the UK. This would apply, for example, in jurisdictions where citizenship is granted on the basis of birth (such as the US and Canada). A passport from that country can then be obtained to travel – this is a quicker process than establishing British citizenship to obtain a British passport.

However, if a visa is required, entry into the UK will depend upon the application of the Immigration Rules or the discretion of the Secretary of State. There are two processes here: a child can enter within the Immigration Rules (where the conditions are met), or the Secretary of State can exercise their discretion to allow entry outside of the Rules.

The Immigration Rules state that a child can obtain a visa to enter the country where at least one intended parent is a legal parent under nationality law (as discussed above) and the surrogate has renounced her parental rights. This appears to offer no practical advantage, and consultee responses indicate that this route is not commonly used, because in such circumstances the child could be registered as a British citizen and obtain a British passport.

However, it is also possible for the child to enter the UK outside of the Immigration Rules at the discretion of the Secretary of State. In order to obtain such entry clearance, the following must be satisfied:

- The intended parents wish to bring the child into the UK to make a parental order application within 6 months of the child’s birth.

- The intended parents can satisfy the parental order requirements.

- One intended parent must be the genetic parent of the child. They do not need to be a legal parent: this would therefore be appropriate where the surrogate is married, and her spouse is the legal father.

- The surrogate has renounced her parental rights.

If the child does not have a British passport or a passport issued in the country of birth, the ability for the child to enter the country is dependent upon entry clearance as well as the issuing of a travel document, Form for Affixing a Visa (FAV).

The recommendations

- As with registration of citizenship and passport applications discussed above, it is recommended that it be possible to open a file for a visa of FAV prior to birth. Again, this should reduce the amount of time post-birth spent on completing the documentation.

- It is recommended that the Home Office provide clear, and up to date, guidance on the documentation required for the application. The guidance has not been updated since 2009, and does not reflect changes in law and practice since then.

- Rather than continue with the Secretary of State exercising discretion for those outside the Immigration Rules, it is recommended that the Rules be updated to provide a route for entry for genetic intended parents who intended to apply for a parental order.

- At present, the ability to obtain a visa is dependent on the surrogate and child having ‘broken ties’. This is no longer applied in practice, and is contrary to recognition of the importance of the relationship between the child and surrogate. As such, it is recommended that this requirement be removed from the Immigration Rules.

Comments

The Law Commissions recommendations relating to international surrogacy arrangements have to strike a careful balance. On the one hand, they have made clear their concerns over international arrangements, with an overarching aim of the recommendations being to encourage intended parents to engage with surrogacy domestically rather than crossing borders. On the other, there needs to be acknowledgement that international arrangements are common, and unlikely to cease.

These recommendations are mainly operational – as such, they would not necessarily encourage intended parents to engage with international surrogacy, but rather ease the process for those who would pursue it anyway. As discussed in an earlier post, by not making any recommendations in relation to allocation of legal parenthood, the Law Commissions can be seen as maintaining their stance that domestic surrogacy remains best protective of the interests and rights of all parties involved.

However, the recommended changes are nonetheless positive. The complexity of differing nationality rules, alongside the interplay of guidance from the separate governmental departments means that entry into the UK for surrogate-born children is far from clear. Having up to date guidance from the Home Office, with the ability for intended parents to commence the application prior to the child’s birth, will hopefully make the process more transparent, timely and less stressful.

Given that the majority of the recommendations are operational, and would not require a change in the legislation, there is also the possibility that these changes could be implemented before any new law is enacted. If there is the will of the Home Office and UK Visa and Immigration Service, intended parents who have engaged with international surrogacy might be able to benefit from revised processes sooner than it would take for legislative reform to take place.

Leave a comment