Welcoming a new-born into the world is a life-changing moment that requires time and care for both the child and the parents. In recognition of this, statutory maternity/paternity leave and pay provisions have been established to ensure that new parents can take time off work to nurture and bond with their babies. However, the current legislation, centred around pregnancy and birth, falls short of adequately addressing the rights and needs of intended parents, leaving them without secure legal entitlements to take time off work and receive financial support. This disparity creates a significant financial burden for intended parents, adding to the challenges they already face in building their families through surrogacy.

Resultantly, the Law Commissions homed in on the effect of surrogacy on employment provisions, focusing on three key areas:

- Operation of statutory maternity and paternity leave and pay;

- The current entitlement of the intended parents to statutory adoption leave;

- The time off work prior to the birth of the child.

Ultimately, the Law Commissions’ recommendations in their Final Report aim to ensure the surrogate’s rights are protected to the same extent as other pregnant women, whilst also ensuring intended parents are treated the same as any other parent within the workplace.

Statutory maternity leave and pay

Leave:

Statutory Maternity leave is the legal entitlement for a woman to take time off work to spend with her new-born child. Currently, entitlement to maternity leave is based on pregnancy and birthing of the child. Therefore, it is not available to intended parents, who, in most cases, will be caring for the child. This is problematic as intended parents are not protected in law to take time off work to spend with their child, which would be in the child’s best interests.

The current law provides that surrogates are entitled to 52 weeks maternity leave, the same as any other pregnant woman. Whilst they are not obliged to take the full duration, a compulsory two-week leave after birth is required. Following this, surrogates are free to return to work at their discretion. Importantly, a surrogates’ entitlement to leave is not contingent on a minimum employment term or similar prerequisites. This is beneficial as it awards the surrogate fair and consistent protections throughout and after their pregnancy.

Pay:

Under the current law, the surrogate is entitled to 39 weeks of maternity pay. However, this entitlement is conditional and subject to meeting specific criteria. If the surrogate cannot meet the criteria for maternity pay, she may be eligible for Maternity Allowance, which is subject to alternative conditions. Statutory maternity pay is not available to intended parents as the eligibility criteria is based on pregnancy, and birth of the child.

Statutory paternity leave and pay

Leave:

Statutory paternity leave and pay provisions apply to the father or second parent of the child. The eligibility criteria for paternal leave and pay have been recognised by the Law Commissions as problematic for the surrogate’s spouse/civil partner because it is dependent on a link with the child, which most surrogate partners will not have. Resultantly, surrogates’ partners have little chance of acquiring statutory leave or pay despite, in most cases, playing a large role in the surrogate’s recovery pre- and post-birth.

To qualify for statutory paternity leave, the person must be either:

- The child’s legal father; or

- The spouse/civil partner of the child’s mother (but not the father)

Further, to attain paternity leave there is an additional condition. They must also have, or expect to have:

- If it’s the child’s legal father, the responsibility for the upbringing of the child; or

- If he or she is the mother’s husband, civil partner, or partner, but is not the child’s father, the main responsibility (besides that, if any of the mother) for the upbringing of the child.

Thus, the legislation leaves little scope for intended parents or the surrogate’s spouse/partner to acquire statutory leave.

Pay:

A further issue with current provisions is that those entitled to statutory paternity leave are those entitled to statutory paternity pay. Thus, surrogate’s partner must have either a genetic relationship with the child or intend to raise the child to acquire any paternity leave or pay. However, in a surrogacy situation, the surrogate’s spouse or partner has virtually no chance of fulfilling the necessary requirements. This is recognised by the Law Commissions, as within the Final Report they expressed how the unavailability of paternity pay/leave is inconsistent with the purpose of the legislation, specifically “caring for the child, or supporting the mother” (emphasis added).

Overall statutory leave and pay presents challenges for intended parents and the partners of surrogates. Maternity leave is based on pregnancy and childbirth, excluding intended parents, and the eligibility criteria for paternity leave also restricts surrogates partners from obtaining leave or pay.

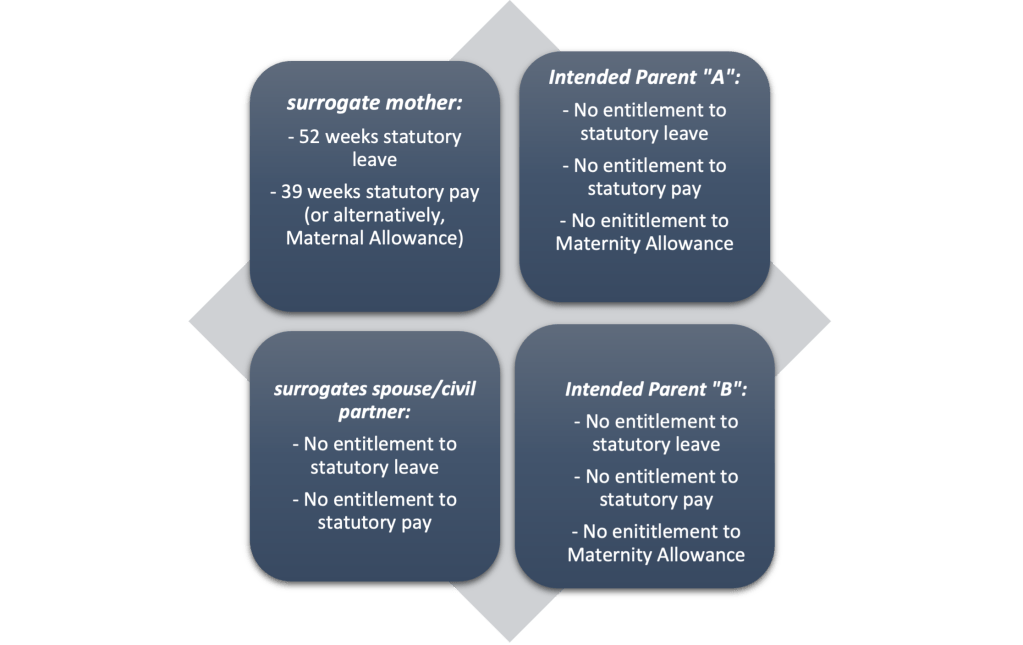

Below is a graph charting the rights and entitlements of surrogate parties regarding leave and pay under the current legislation:

In the 2019 Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions asked consultees whether the statutory paternity pay/leave legislation, and it’s application to the surrogate’s spouse needed reform. From the consultation responses, the Law Commissions in their Final Report stated that they could not justify the extension of statutory paternity leave or pay, and no longer recommend this.

Instead, they suggest including in the permitted category of expenses for intended parents to be able to pay the surrogate for actual loss of earnings, or potential loss of earnings, for a person who takes time of work to support the surrogate post-birth (up to two weeks). It is envisaged that this could be the surrogate’s spouse or partner, but could apply more broadly to a friend or relative.

Adoption leave and pay

As established, under the current law intended parents are not entitled to statutory maternity or paternity leave and pay because this is applies to women who are pregnant, and their partners. However, since 2015 intended parents have been recognised as potentially entitled to statutory adoption leave and pay. The entitlement under the adoption provisions are the same as the maternity provisions. Whilst intended parents will not usually be required to adopt the surrogate-born child, the applicability of the adoption leave and pay provisions provide an important safeguard for intended parents.

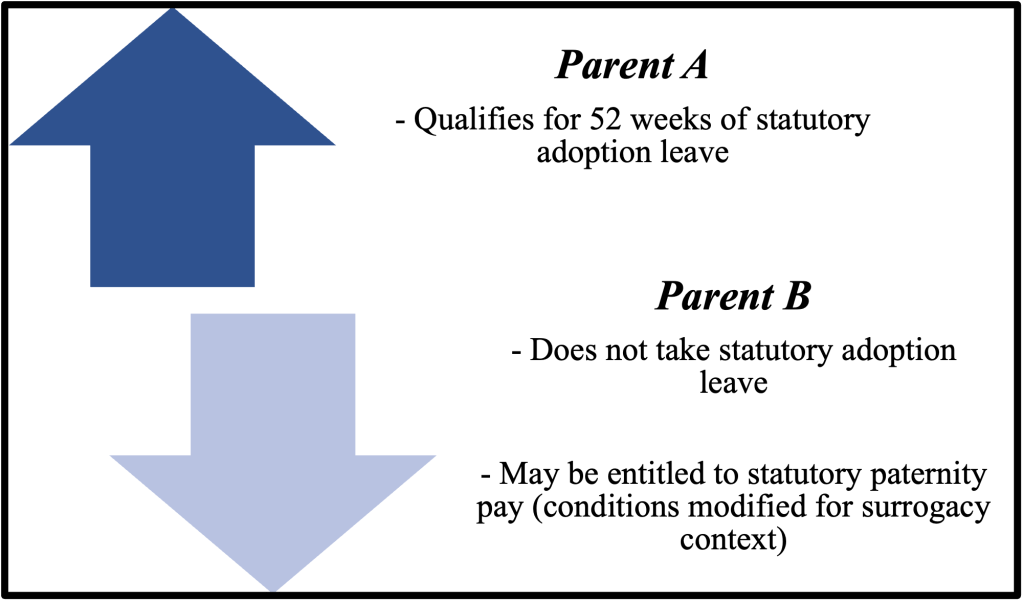

Entitlement to statutory adoption leave and pay under the current law requires the parents to be defined as “Parent A” and “Parent B”. Therefore, only one parent can obtain adoption leave and pay (Parent A), and the other may be eligible for paternity pay (Parent B). The allocation of Parent A and Parent B can be decided by the intended parents themselves.

Parent B will qualify for statutory paternity pay if:

- he or she is either married to, the civil partner of, or the partner of Parent A; and

- he or she has, or expects to have, the main responsibility (apart from the responsibility of Parent A) for the upbringing of the child.

The current law therefore affords intended parents the same rights as people having a child via other routes, which is in-line with the Law Commissions recommendations for surrogacy to be seen as another way to start a family.

However, intended parents’ employment rights may be affected by the implementation of the new pathway, discussed in an earlier post, as both intended parents are made the legal parents at birth. Resultantly, one intended parent may qualify for the standard statutory paternity leave (provided conditions are met) because they will be the child’s father and have responsibility for the child, as required by the existing paternity leave regulations. Consequently, provisions outlined for Parent B may be rendered unnecessary; however, the alternative intended parent would still be able to claim adoption leave.

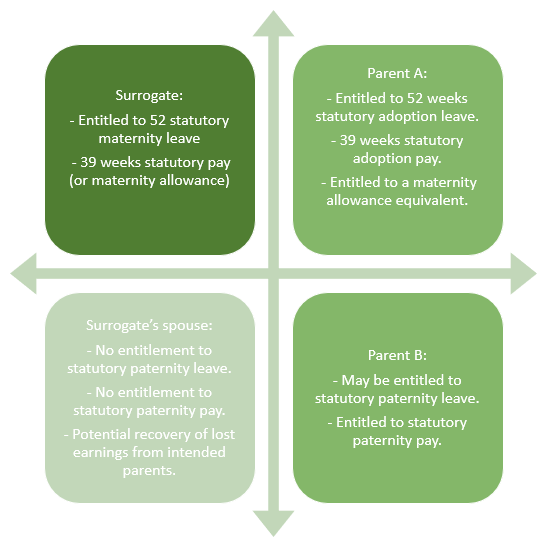

Following the recommendations from the Law Commissions, below is an updated graph of what the respective parties’ rights and entitlements would be if implemented:

Maternity Allowance

Maternity Allowance is a weekly payment eligible for women who were employed, or self-employed for some time prior and during her pregnancy. Maternity Allowance is primarily aimed at self-employed mothers, but it also benefits mothers who are employed but cannot fulfil the conditions for statutory maternity pay.

S.35(1) of the Social Security Contribution and Benefits Act 1992 (The 1992 Act) and provides an allowance where ‘a woman has engaged in employment, as an employed or self-employed earner for any park of the week in the case of at least 26 of the 66 weeks’.

When it comes to surrogacy arrangements, intended parents are left without an equivalent benefit, highlighting a significant gap in the current legislation. The Law Commissions acknowledged the inconsistency of denying intended parents an equivalent of Maternity Allowance as they emphasise within the Final Report that employment law should grant the same rights to those involved in surrogacy pregnancies as those involved in other forms of pregnancy.

To address the gap where intended parents in surrogacy arrangements are not entitled to statutory adoption pay, the Law Commissions recommend the implementation of an equivalent allowance which would follow the current eligibility criteria for Maternity Allowance. This means that intended parents seeking the benefit should have been engaged in employment or self-employment for at least 26 out of the 66 weeks preceding the relevant week. The definition of intended parent would be those who become parents through the new pathway or the parental order process.

The Law Commission’s recommendations include aligning the definition of statutory adoption pay for intended parents with the existing criteria, which requires 26 weeks of continuous employment ending with the relevant week. Additionally, it is suggested that the payment period for the benefit should commence on the same terms as statutory adoption pay. This means that in a surrogacy situation, the benefit would begin on the day of the child’s birth or the following day if the person is at work on that day.

Furthermore, in the Final Report the Law Commissions propose allowing intended parents to begin statutory adoption leave and pay up to 14 days before the expected date of the child’s birth, aligning with the rights of adoptive parents. The suggested equivalent benefit should be paid at the same rate as Maternity Allowance for pregnant women. The Law Commission also highlights the need to extend the possibility of claiming the equivalent benefit to intended parents who work with a self-employed spouse or civil partner and meet the necessary eligibility criteria. However, the benefit can only be claimed by one of the intended parents.

Pre-birth leave entitlement

Under the current provisions, intended parents can only commence their statutory leave (and thus pay entitlement) on the day that the child is born. This differs from those who would be entitled to statutory maternity pay, and from those who become parents through adoption, who can begin their leave up to 14 days before the expected date of birth.

To address this anomaly, the Law Commissions recommend that intended parents should be able to commence their statutory adoption leave and pay 14 days before, aligning with the rights of other parents.

In relation to other leave entitlement prior to the birth of the child, the Consultation Paper initially focused on induced lactation leave, but based on consultation responses, a broader examination of leave entitlements for intended parents before birth was undertaken in the Final Report. Currently, intended parents are entitled to unpaid time off for two ante-natal appointments, totalling 6.5 hours each. In contrast, adoptive parents have a more comprehensive leave policy, including both paid and unpaid time off. A sole adoptive parent or one of two joint adoptive parents can take paid leave on five occasions, while the other parent can take unpaid time off on two occasions. The maximum duration for each occasion is 6.5 hours.

The Law Commissions are therefore recommending that pre-birth leave entitlement for intended parents is aligned with the adoption provisions, allowing for intended parents to attend ante-natal appointments with the surrogate.

Commentary: achieving parity?

In conclusion, the Law Commissions’ Final Report addresses the current problems faced by intended parents in employment law. The recommendations aim to resolve disparities in the law, recognising the rights and needs of parties, through widening the scope for intended parents to obtain financial support and ensuring they have appropriate time off work to spend time with their child. However, surrogates’ partners would see less protection under the recommendations, with the removal of statutory paternity provisions, instead relying on intended parents to cover loss of earnings for supporting the surrogate post-birth.

Overall, the extension of statutory adoption leave and pay, and creation of a maternity allowance equivalent, for intended parents fulfils the Law Commissions aim of aligning intended parents with adoptive parents’ rights. The recommendations are a step toward in affording intended parents fair and equitable rights within the workplace, and will enhance the welfare of the child by supporting intended parents in being able to take the time needed to bond and care for the child.

Leave a comment