Parental Responsibility is a legal responsibility all parents have at birth of their child. In addition, the court can grant parental responsibility to other adults involved in the child’s life where they deem it appropriate. Parental responsibility confers individuals the right to exercise decisions over the child’s day-to-day care, and appoints them individual and financial responsibilities, amongst other things. Currently, parental responsibility can be held by multiple parties at once, but each can make individual decisions about the care of the child.

Current law

Within the current legal framework, the surrogate is the legal mother at birth, therefore she automatically obtains parental responsibility for the child, whereas the intended parents do not. Intended parents currently acquire parental responsibility by way of a parental order, granted by the court, allocating the intended parents as the legal parents, or where a parental responsibility order is made. This period in between birth and the granting of a parental order is called the ‘interim period’. Intended parents’ absence of parental responsibility at birth is problematic, as intended parents may have to wait several weeks (if not longer) to obtain legal responsibility for their child, therefore having no legal backing to make decisions over the child. This is particularly significant in relation to the child’s medical care. Furthermore, as the intended parents lack parental responsibility they do not have any legal requirement to care for the child. Resultantly, the surrogate’s position is precarious as she remains responsible for making decisions about the child who she is not likely to have care of. The surrogate’s parental responsibility will only be removed by the court when she has given her consent to a parental order being granted.

The Law Commissions recognised that this approach to parental responsibility may not be in the best interests of the child, and it requires the surrogate to be involved in making decisions about the child post-birth, when she herself does not view herself as the parent or have any intention of parenting the child. It also leaves surrogates in an unstable position post-birth, where she could potentially be left out of pocket and caring for the child against her wishes.

The Recommendations: who would have parental responsibility?

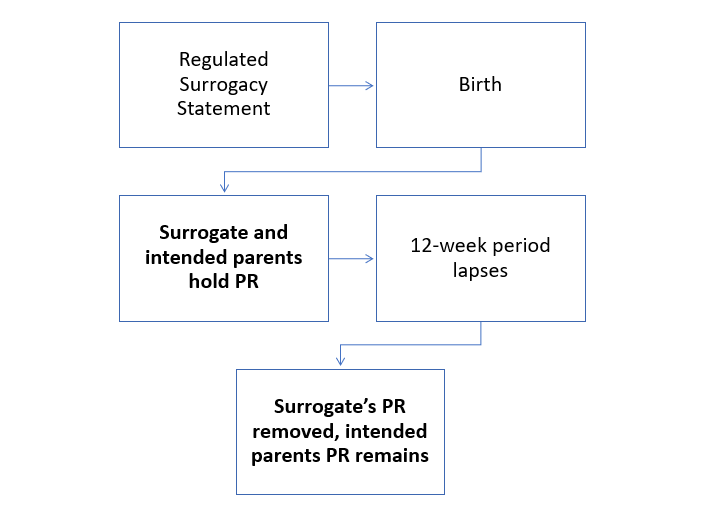

One of the key recommendations of the Final Report is the new pathway. On the new pathway, intended parents would no longer need to obtain a parental order from the court. Instead, the Law Commissions recommended that intended parents would obtain legal parenthood at birth, therefore automatically obtaining parental responsibility. Additionally, surrogates would also be conferred parental responsibility at birth, meaning all three parties would be supported by law to exercise decisions about the child.

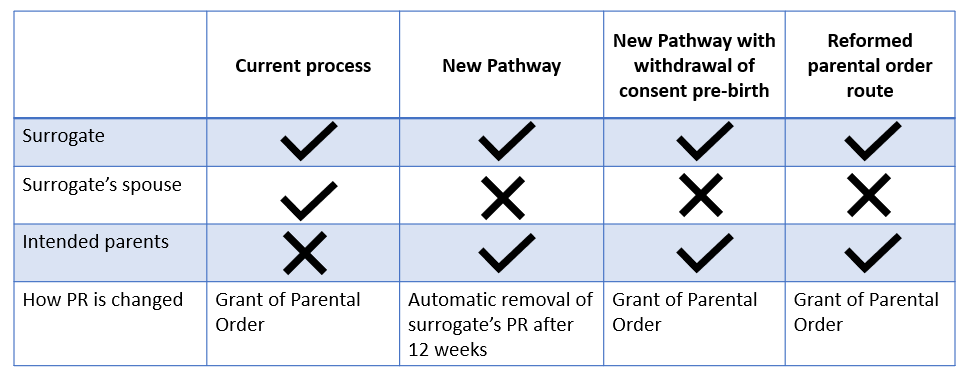

Below is a table illustrating the status of parental responsibility for surrogates and intended parents under the current law, and how this would change under the recommendations in the Final Report:

Parental responsibility on the new pathway: Intended parents to obtain parental responsibility from birth

As displayed, a fundamental change within the Final Report is that surrogacy arrangements on the new pathway will give intended parents parental responsibility over the child at birth, in conjunction with the surrogate. This means that the intended parents and the surrogate will all hold parental responsibility, and can legally make individual decisions about the child. Resultantly, there will be an additional layer of security for both parties within the agreement.

The Law Commission suggest that intended parents on the new pathway are to acquire parental responsibility through their legal parenthood, inherent to the pathway. As a result, intended parents need not apply to the court for a parental order, removing the burdensome process of trying to acquire legal rights for a child which they are most likely caring for.

In relation to surrogates, in the Final Report the Law Commissions recognised that many surrogates may not want to retain parental responsibility for the child, but nevertheless held the view that it is important for them to retain parental responsibility at birth. To do otherwise would be to make the surrogate ‘a legal stranger to the child,’ resulting in the surrogate being reliant on a court order, or alternatively the consent of the intended parents, to have contact with or care over the child. Furthermore, a surrogate must also be able to retain parental responsibility in the scenario that she may choose to withdraw her consent to the surrogacy agreement, as otherwise she will have no legal ability to care for the child during the period in which she would need to apply for a parental order. Consequently, the Law Commissions drew a balance between these opposing issues, recommending in the Final Report that surrogates retain parental responsibility for six-weeks post-birth, in line with the period in which they may withdraw their consent.

In the scenario that the surrogate does withdraw her consent, the Final Report recommends that the intended parents would remain the legal parents of the child, retaining parental responsibility if they are caring for the child at the time of withdrawal. The surrogate would also retain parental responsibility and may seek a parental order, in which case her parental responsibility would either cease or remain depending upon the court’s decision. However, in most cases the court will favour the intended parents and the surrogate’s parental responsibility would be removed.

Parental Responsibility for arrangements not on the new pathway

In the Consultation Paper, the Law Commissions provisionally proposed that where a child is born of a surrogacy arrangement outside the new pathway, the surrogate would continue to have parental responsibility, and the intended parents will acquire parental responsibility where

(a) The child is living with the intended parents or being cared for by them; and

(b) They intended to apply for a parental order.

Subsequently, in the Final Report the Law Commissions removed the second requirement on the basis that it would be difficult to prove the parties’ intention and that it would be unnecessary as intended parents would automatically acquire parental responsibility if the child is cared for by them. Therefore, intended parents will automatically be granted parental responsibility if the child is in their care.

Further, for agreements not on the new pathway, surrogates would retain their parental responsibility until legal parenthood is established by way of a parental order, or six-months post-birth (as this aligns with when a surrogate’s right to make a parental order lapses).

To cement these proposals, the Law Commissions have suggested that for England and Wales, intended parents are added to the list of persons, in S.10 of the Children Act 1989, who can apply for a child arrangements order, allowing them to be allocated parental responsibility by the court if they meet the statutory requirements. Further, the Law Commissions have also suggested an amendment of S.11 of the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 for the same outcome.

Comments

It is important, to assure fairness and security within surrogacy arrangements, that intended parents may have exercisable rights to make decisions about the child and fulfil their agreed responsibilities. Moreover, as most surrogacy agreements result in the intended parents caring for the child post-birth, it only makes sense that the law aligns with common practice.

Equally, however, it is important that a surrogate is protected within law if she changes her mind and wishes to withdraw her consent from the agreement. This ensures that the surrogacy agreement remains unenforceable, and the surrogate retains her autonomy throughout. Further, it is within the child’s best interests for neither the surrogate or intended parents to experience emotional distress from disputes, which could result from the lack of responsibility intended parents have under the current law.

Overall, the Law Commissions appear to be advancing the protection of rights of both the surrogate and the intended parents through their recommendations, whilst securing the child’s best interests through the intended parents having parental responsibility at birth.

Leave a comment