Before being able to consider the Law Commissions’ proposals and report, it is worth restating the current legal framework to better understand why a review and reform of the law was deemed necessary.

Surrogacy arrangements

A surrogacy arrangement is when a woman agrees to carry and give birth to a child with the intention for the intended parents to become the social and legal parents of the child once born. There are two forms of surrogacy: genetic (or ‘traditional’) which involves using the surrogate’s own eggs to form the embryo, and gestational, whereby the surrogate has no genetic link to the child, with the embryo being formed from the egg of the intended mother or a donor.

In England and Wales, there are some key legal rules relating to these surrogacy arrangements. First, surrogacy agreements are unenforceable. This means that a surrogate cannot be forced to give the child to the intended parents, nor can the intended parents be forced to take over the care of the child. In the view of some, this means surrogacy is precarious – however, in the vast majority of cases, the arrangements are smooth and the intention of all parties are met.

Secondly, surrogacy is only permitted on an altruistic basis with a prohibition on commercial practice. This means that surrogacy organisations and agencies are not permitted to operate on a commercial basis. Within the current legal framework, the only money that the surrogate can receive is for ‘reasonable expenses’, unless retrospectively authorised. This may cover things such as travel costs, private healthcare and childcare. However, the case law demonstrates the reality that the court interpret reasonable expenses very broadly, and are willing to authorise payments beyond reasonable expenses if the child’s welfare requires it. This will be a key aspect for the Law Commissions’ report to address.

Parenthood following surrogacy

Arguably, the most important legal question following a surrogacy arrangement is how legal parenthood is attributed. Legal parenthood is important because it determines who has parental responsibility and can make decisions relating to the child, as well as impacting on associated issues such as nationality and inheritance.

The latin maxim used in England and Wales is mater semper certa est: thistranslates as ‘the mother is always certain’. When a child is born, the person who gives birth to the child is the legal mother. This is the case regardless of whether that person is genetically related to the child or intends to act as a mother to the child. This means that when a child is born as a result of the surrogacy arrangement, the surrogate is treated as the legal mother.

As for the father or second parent, there is a common law presumption that the husband of the mother is the legal father. This presumption is enshrined in statute, and applies equally to same-sex spouses so that the wife would be the second parent. Resultantly, if the surrogate is married, her spouse would be the second parent.

If the surrogate is not married, it is possible for one of the intended parents to be listed as the second parent – either as a result of being genetically related to the child or through meeting the statutory requirements of the agreed fatherhood or agreed second parent conditions. Whilst this allows one intended parent to be recognised as the child’s legal parent, this in itself is insufficient because the surrogate retains legal parenthood and if there are two intended parents, one of these would remain without parental status.

This allocation of parenthood is therefore obviously problematic in a surrogacy context because the individuals who commissioned the pregnancy and intend to act as the child’s parents will not automatically be the legal parents. As such, the intended parents have to apply for a parental order. The parental order process involves the intended parents applying to the court for parenthood to be transferred from the surrogate (and her spouse, if applicable) to the intended parents. Once the order is granted, the birth certificate is re-registered listing the intended parents as the legal parents.

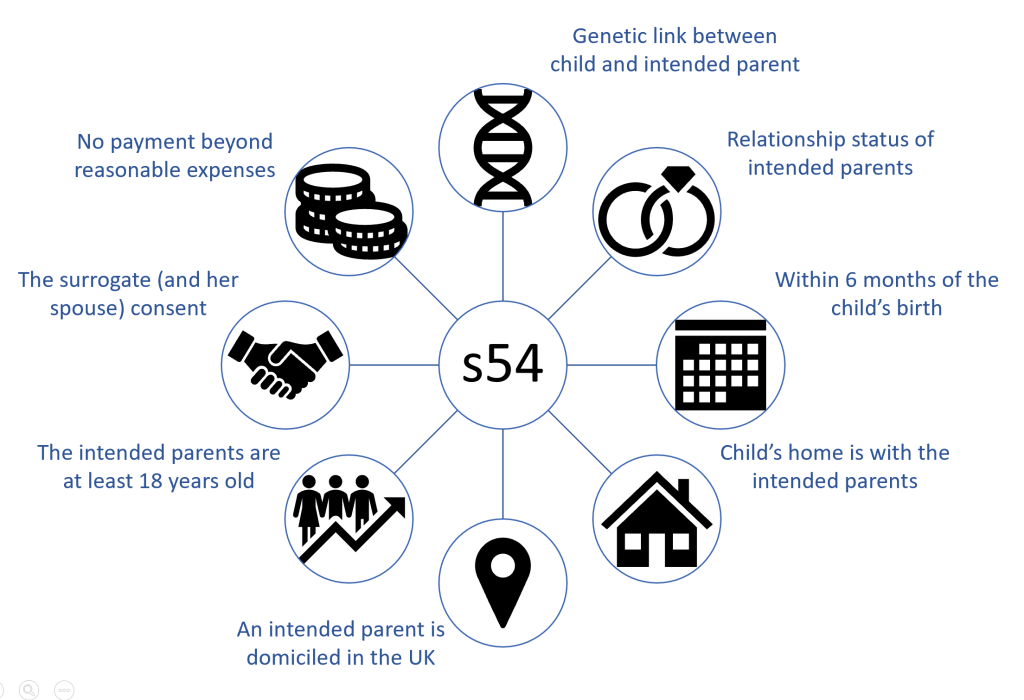

Parental order requirements

In order for the court to be able to grant a parental order, the statutory requirements contained within s54 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 need to be met. Since 2019, a single intended parent has also been able to apply for legal parenthood, with the requirements contained within s54A. Alongside these requirements, the court also has an obligation to ensure that the decision will meet the lifelong welfare needs of the child.

The prescriptive requirements contained within s54 have been subject to much judicial interpretation and academic criticism. This is because, in circumstances where the child is living with the intended parents, a failure to meet one of the requirements could prevent a parental order being granted contrary to the best interests of the child. As a result, there are some requirements which have been set aside, or very liberally interpreted, by the court to still allow a parental order to be granted.

One example of this liberal interpretation is the requirement for the parental order to be applied for within 6 months of the child’s birth. In the seminal case of Re X (A Child) (Surrogacy: Time Limit), it was stated that it would be ‘nonsensical’ to prevent a parental order from being granted as a result of being out of time. The parental order was granted despite the child being older than 6 months, and in cases since then, parental orders have been granted to children in their teens, and even recently, to an adult individual.

Alongside the time limit, other requirements, such as for the child’s home to be with the intended parents and for no more than reasonable expenses to have been paid to the surrogate, have been interpreted to such an extent that it could be argued to be a disregard for the statutory criteria. In such circumstances, however, the decision can be justified on the basis that the child’s welfare necessitates the order to be granted, allowing legal parenthood to reflect their lived reality.

Other requirements, however, have not been interpreted with the same level of flexibility. Requirements such as for an intended parent to be domiciled in the UK, for there to be a genetic link between an intended parent and child, and for the surrogate to consent to the granting of the parental order, have been regarded as mandatory by the court, with instances where a parental order has been refused due to one of these requirements not being satisfied.

The retrospective nature of the parental order process leaves the court in a difficult position. By the time the court comes to review the case, the child will often have formed a close bond with the intended parents. The obligation on the court to reconcile the s54 requirements against the welfare of the child has led to the situation where precise legislative wording is being deviated from. For this reason, the allocation of parenthood following surrogacy is at the forefront of many minds in relation to the reform proposals.

Leave a comment